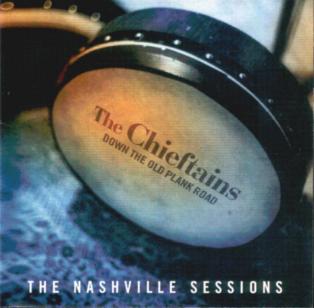

The Chieftains

Down the Old Plank Road – The

Nashville Sessions

RCA Victor 09026-63971-2; 54 minutes; 2002

This is not so much a review as an article based on an

interview with Paddy Moloney in the

Autumn of 2002.

Time passes quickly in a conversation with Paddy Moloney,

not just through the pleasure of chatting to the man, but because of his innate

sense of his own and his music’s roots. So when the song Dark As a Dungeon

enters the arena, Paddy whisks me back to the early 1950s and a man called

Charlie Tyndall who “went around all the fleadh cheoils singing these songs and

later became one of my Three Squares” and then quickly forward to Vince Gill

and the version that appears on The Chieftains’ latest CD.

Down the Old Plank Road is The Chieftains’ fortieth album in forty years (and that’s not counting the plethora of compilations) and follows their aptly titled own celebration of those decades, The Wide World Over. In that time The Chieftains established themselves on the international stage as the foremost ambassadors of Ireland’s traditional music while becoming increasingly known for their willingness to experiment and cross musical boundaries. In their time they’ve recorded collaborations with Chinese, Breton, Canadian and Galician musicians, while also working with performers as various as Ry Cooder, Mick Jagger, Diana Krall and Chito Kawachi. In 1992 came their Nashville album, Another Country, and earlier this year the band was back in Texas again. “There were plenty of out-takes from that album,” says Paddy, “and it was always my intention to make a second one, but to be a little more authentic and include more bluegrass.”

Authenticity has always been an issue for Paddy Moloney and, of course, Ireland’s traditional music hardliners. It all began when he was six years old (“My mother bought me one of those little tin whistles for one shilling and ninepence and I haven’t looked back since”) and he subsequently moved on to the uilleann pipes, learning the complexities of this instrument under the tutelage of one of Ireland’s most renowned pipers, the late Leo Rowsome. For Paddy the pipes are a solo, creative instrument – “it’s the most contrary instrument – you have to be crazy to play the damned thing! It’s very temperamental too – it’s meant to be taken home and looked after, not played on the Great Wall of China!”

Growing up in Donnycarney in Dublin’s Northside he learnt other music from the radio, though there was always the excitement of a visit to his grandmother’s three-roomed cottage in County Laois. “The neighbours would arrive in the evening, open the door and sit down unannounced. They’d play cards and then the melodeon would come down from the dresser and people would dance. There might be forty or fifty people spilling out into the yard and it would go on till all hours in the morning. There’d be a round of waltzes at about six or seven, finishing off with The Tennessee Waltz and someone would sing I’ll Be All Smiles Tonight – I gave that one to Martina McBride to sing on Plank Road.”

In his teens he won four All-Ireland championships on his traditional instruments, but also formed groups such as The Happy Wanderers and The Three Squares. The latter was a skiffle group, in which Paddy played both ukulele and washboard, but he couldn’t resist introducing the whistle or the pipes to play reels during songs such as ‘Putting on the Agony’ and other Lonnie Donegan classics. He formed and played in céilí bands such as the Lough Gowna and the Shannonside, but began putting together something a little bit different in the mid-1950s.

“I was more interested in the combination of instruments. I could hear harmonies and would play counter-melodies, “he remarks, adding “which was a little bit off the beaten track for the purists.” The banjo-player Barney McKenna (forty of his own years with The Dubliners) was one of those first involved, but others were recruited from elsewhere on the traditional circuit, some as a consequence of Paddy’s involvement in Seán Ó Riada’s own experimental group, Ceoltóirí Chualann.

The ultimate result was the appearance in 1962 of an album simply called The Chieftains (now universally known as Chieftains 1), but the band remained part-time musicians until the mid-1970s and the increasing success of their concerts, such as a sell-out St. Patrick’s Day gig at London’s Albert Hall in 1975, and the soundtrack for the film Barry Lyndon. The band’s last line-up change occurred in 1979 and Paddy’s fellow members consist of flute-player Matt Molloy (flute), the singing and bodhrán of Kevin Conneff, the harper and pianist Derek Bell and the fiddlers Seán Keane and Martin Fay (though the latter is now ‘semi-retired’).

Irish Heartbeat, their immensely popular collaboration with Van Morrison, came in 1988, but it was the appearance of Another Country four years later which caused some traditional hackles to rise. Down the Old Plank Road will add further fuel to the debate about the impact of Ireland’s population diaspora on the world’s musical cultures.

For Paddy, the links between Ireland and the USA are transparent, indeed he calls the new record his “blue-green-grass album, the blue and green grass of home, though I can’t imagine Tom Jones singing that.” As an example he cites first the centuries-old Irish song Rosc Catha na Muimhain (“The Battle of Munster”) whose melody seems to appear in various bluegrass numbers. One such is the song Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down, sung by Lyle Lovett on the album. All the other thirteen tracks were recorded in Nashville with the likes of musicians such as Béla Fleck and Jeff White who’d arranged for the studio to be decorated in such a way that it was like “being back at your granny’s or in your own parlour.” Lyle, however, had come off second-best in a confrontation with a bull on his ranch and been hospitalised as a result, so Paddy popped down to Austen and Lyle made it to the studio in a special chair.

Tracing and hearing the connections between Irish and American music also bore fruition in the appearance of the banjo-player Earl Scruggs whose wife apparently phoned Paddy to say “My Earl would like to come down and record”. As Paddy notes, “How could you refuse the likes of Earl Scruggs (or his wife)?” and Earl chose to play the tune Sally Goodin which features four or five Irish reels rolled together. Others appearing on the album include Ricky Scaggs, The Del McCoury Band, Alison Krauss and the more leftfield Gillian Welch.

Some have remarked that The Chieftains were the first ever world music band and it’s tempting to pose the question to Paddy. “That’s the first time I’ve ever had that put to me,” he replies, pondering before agreeing that it might possibly be fair comment. But for him it’s all about “great music from around the world” and not just some back-of-the-shelves record company categorisation. “It’s about how music began, the roots of the whole thing and it deserves a whole lot better. It should be more fun, presented right and given a hearing.”

As for his plans for the future, well enough grand music came out of the Nashville sessions to release a second album next March and then there’ll be a tour with the musicians who took part. He’s continuing to compose soundtracks (recent outings include Of Gods and Generals and The Gangs in New York) and then there’s the ongoing solo album project. It’s more than thirty years since he was one of the uilleann pipers playing solo on the essential The Drones and Chanters and almost as many since the Tin Whistles album made with Seán Potts, so his own solo venture is long overdue. “Ah”, he sighs, harking to the pipes’ complexities, “if I could just get my reeds right”.

This article by Geoff Wallis originally appeared in Songlines magazine – www.songlines.co.uk.