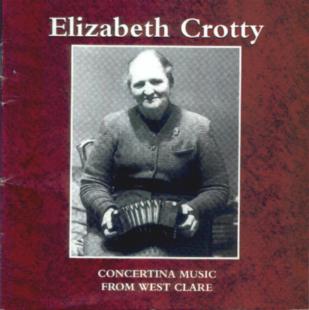

Elizabeth Crotty

Concertina Music from West Clare

RTÉ 225CD; 47 minutes; 1999

Single

girl, single girl, she’s going where she please - Married girl, married girl,

baby on her knee.

from Single Girl, Married Girl, by The Carter Family, Victor 20937A

By any standards this is an important release. It is

important for three good reasons. Firstly, Mrs Crotty was an exceptional

musician. Her vigorous playing on these recordings utterly belies her age

at the time they were made. Secondly, she was an important link with

traditions and practices surrounding music and dance, from the era which

stretched between the famine and the phonograph. Finally, her career, and

her standing within Irish music, anticipated the changing status of women

musicians in Ireland generally. For most of Mrs Crotty’s life span, women

musicians were few in number. Those who did play were generally ignored

and undervalued and forced to accept a lower social profile than men. Yet

she became such a celebrated personage in the world of Irish music, that her

death occasioned a telegram of condolence from the President of Ireland.

To place these points in context, some retailing of Michael Tubridy’s booklet notes is in order. So is a fair amount of conjecture on my part, for the notes at times are distinctly short on facts and conclusions. The booklet tells us that Elizabeth Crotty was born in 1885, the youngest member of a musical family who lived in the Cooraclare district of South Co Clare. Although apparently entirely self taught, she seems to have mastered the concertina early in life, and to have become a popular player at house dances in the region. This information is significant for, in Mrs Crotty’s day, women house dance musicians were very much the exception. This is partly a matter of simple statistics; for the first half of the twentieth century, women musicians in Ireland were heavily outnumbered by men. However, the effects of this numerical imbalance were compounded by the low status which women then occupied, making what few women musicians there were even less prominent. To further emphasise the status quo, patterns of attendance at house dances displayed a similar unequal sex distribution. Dancing, in fact, was the preserve of married and single men, and of single women. Once a woman married she was expected to stop at home and keep house, and to give up dancing and any form of public music making. It is not surprising therefore to learn that Mrs Crotty did not marry until she was around twenty-nine. Late marriage was common in rural Ireland, and twenty-nine would have been no great age. Nevertheless, it suggests that Mrs Crotty possessed a degree of freedom to attend and play for house dances, which would not have been shared by her married confreres. We begin to see the emergence of a singular musical personage, as well as a talented one.

This singularity might have been carried over into her married life. Her spouse, Miko Crotty, was a returned emigrant from the United States, a factor which suggests that the Crottys could have started married life with a fair measure of affluence. Emigrants did not typically return to their homeland unless they had something to show for their labours abroad. Be that as it may, this couple were able to set up a pub in Kilrush, the nearest sizeable town to Cooraclare. The booklet retails several musical events at the Crotty’s pub; the impression, that it was a prominent centre for music, with Mrs Crotty at the heart of things, being strengthened by her entry in The Companion to Irish Traditional Music1. The entry, again written by Michael Tubridy, but this time with the assistance of Mick Kinsella, describes the establishment as “a famous music ‘house’”.

A claim like this needs to be carefully considered, for the playing of music in Irish pubs did not become widespread until some years after Mrs Crotty died. It is also important to consider the roles which convention and social restraint and reputation typically played in rural and semi/rural societies. To put it another way, tradition and precedent offered models of conformity which people were expected to adhere to. One would therefore expect to find major inhibiting factors undermining Mrs Crotty’s participation in music once she was married. Against these points however, there is the lady’s love of music. It is possible to imagine that a pub under her jurisdiction would be at least a partial exception to the general rule. Indeed, one can envisage the life of a pub landlady combining with music making on her own premises far more readily than had she, say, married a farm labourer. It is in short conceivable that pub ownership was another key feature in Mrs Crotty’s musical development, and that it presented opportunities for music and dancing which would not have been available to her otherwise. If so, then it is also possible that the name of Mrs Crotty would have been spread over a wide section of the surrounding countryside.

A third piece of cogitation unfortunately concerns the state of Mrs Crotty’s health. A medical ailment, unspecified in the booklet notes, necessitated regular trips to Dublin for most of her adult life. These provided her with opportunities to visit the Pipers’ Club in Thomas Street, as well as various other musical venues in Dublin, and thus to mix with an unusually wide circle of players. In an Ireland of restricted travel facilities, this is a facility which would not have been widely enjoyed by rural musicians. As with the possibilities of pub music, therefore, it would have placed her name before an unusually large and disparate audience. Thus there are grounds, albeit vague and conjectural, for explaining Mrs Crotty’s singularity via a chain of exceptional circumstances.

We are, unfortunately, far from finished with conjecture. However, by the late 1940s, enough verifiable detail emerges for us to supplement supposition with fact. For example, it seems to have been as a result of these Dublin visits that she met and befriended the fiddle player, Kathleen Harrington, another prominent woman musician of the day. Mrs Harrington was from Sligo, but was by this time living in Dublin. She was also a founder member of the Kincora Céilí Band and of The Gardiner Traditional Trio and was therefore well known to programme makers at Raidió Éireann. Around 1950 she began to make radio broadcasts with Mrs Crotty. In 1955, probably as the result of these broadcasts, Mrs Crotty was visited by a Raidió Éireann mobile recording unit under the aegis of Ciarán MacMathúna. The booklet tells us that MacMathúna recorded her on several subsequent events, before her death in 1960. The point is not actually spelt out, but it seems to be exclusively his recordings which we hear on this CD.

For the benefit of British readers, I might explain that these recording units roughly paralleled the folk music collecting activities of the BBC during the 1950s. Unlike the BBC, however, Raidió Éireann recordings were not made primarily for archival purposes. Unlike England, where folk music is seen as an odd pastime indulged in by statistically insignificant numbers of musical eccentrics, Raidió Éireann had a serious commitment to a national heritage. These recordings were made for mainstream broadcast entertainment. The function of the outside broadcast vans, for that is what they were, was to record rural musicians who otherwise found it difficult to get up to the studios in Dublin. A measure of scepticism is in order therefore, when assessing the musical significance of such recordings. One might imagine that collectors with such a brief would have gone for star players, rather than attempt to preserve a representative cross section of rural Irish folk music. Equally, one imagines that musicians would have gone for the star items in their repertoires, or else would have played what was uppermost in their minds, or what they thought radio listeners would want to hear. Incidentally, lest I have confused British readers, Raidió Éireann is the old name for what was, with the introduction of television, to become RadioTeilifís Éireann. Hence the initials, RTÉ.

With thoughts of Raidió Éireann’s collecting policies in mind, let us for the moment leave off hypothetically studying Mrs Crotty’s career. Let us turn instead to considering this product of their joint labours. It consists of thirty-one tracks, most of them single tunes, most of them under two minutes long. The playing is quite remarkable. It has an astonishing spirit and a tremendous rhythm, characteristics which alone delineate this music as something exceptional. But it comes across with such beauty and life and colour and passion! One day I will understand how musicians like Mrs Crotty can communicate such a wealth of feeling by the mechanical action of operating a lifeless instrument. In the meantime, I shall content myself with marvelling at these thirty-one tracks. There is so much warmth, so much humanity, so much Gemütlichkeit. The booklet, by the way, contains a short memoir by Ciarán MacMathúna, in addition to Michael Tubridy’s discussion. Both parties bear testimony to Mrs Crotty’s kindly and hospitable nature. I know - I can hear it in the music.

Single melodies were apparently the norm with Mrs Crotty, and that is another important piece of information. They demonstrate that this music is a legacy from the period when its primary function was to accompany dancing. The practice of coupling tunes was largely an innovation of the Irish-American phonograph industry, and it represents a shift of function on the part of the music. That is, record companies, realising that people were buying records to listen to, encouraged the playing of medleys as a way of increasing listenability. Michael Tubridy’s notes do not mention the existence of a tradition of single melodies. Instead, he claims that Mrs Crotty played that way because she had great difficulty changing from one tune to another. There is evidence that this was so, but it does not sound like the whole story. She would have been very near middle age by the time American-made 78s started to impact upon Irish domiciled musicians, and may simply have been unable to adapt to the new way of playing.

But if she never learned how to switch tunes in midstream, she certainly seems to have picked up the habits of modern times and improved communications, in terms of playing with other musicians. Her duet work with Mrs Harrington is not featured on this disc, but Mrs Crotty is heard with a number of other notable players of the day. They include Paddy Canny, Denis Murphy, Agnes White, Peadar O Loughlin, Johnny Pickering and Paddy Breen. It is a rare disc which can assemble such an array of luminaries, and their presence is another very good reason for buying this one. The duets with White, Canny, Murphy and O’Loughlin are wonderful. They are beauty itself. Moreover, the ensemble tracks are imbued with a collective warmth and charm; characteristics so typical of Irish music before it became popularised and internationalised ... and, in consequence, marginalised in my affections. This is Irish music before it became brimful of bodhráns and bongos and banjos and bouzoukis. This is Irish music as it was before anybody ever heard it thrashed as though all the devils in hell were at the heels of the thrashers.

There is a quality of pastoral innocence, of rural modesty, about this music, and about the way it is played. The players are people who are not out to impress anybody with great flashes of virtuosity or dynamics or pyrotechnics. They are as quiet as the music and the music is as quiet and gentle as the Irish countryside. The aura of innocence even extends to some of the titles, as though they belonged to Ireland before the fall; before the serpents of sex and drugs and rock ‘n roll managed to sneak into the country while St Patrick’s back was turned; The Wind that Shakes the Barley, Kitty Gone a’Milking, Rolling in the Ryegrass. However, such beguiling appellations are mixed in with other titles like The Battering Ram, The Green Fields of America and The Flogging Reel. These betoken a different Ireland; one battered by evictions and rack rent and emigration, and the enlistment of its young men into the armed protection of the very country which caused Ireland so much misery. It is both apt and ironic that titles speaking of oppression should occur in such a repertoire. Harsh authority structures of the wider social milieu end up as the model for authority structures within the family. The world over, it is the weakest who bear the greatest brunt.

Getting back to those ensemble tracks - one of the downsides of session playing, without or without the infernal bodhrán, has been the emergence of a standard repertoire throughout Ireland. Indeed, it has come to exist in all the places where Irish music is nowadays played. It is also the only major downside of this disc, at least as far as the performances are concerned. I am not sure how much to make of the distribution of tune types which Mrs Crotty plays here, for Clare is great jig and reel country. Even so, I would not have expected to find these two rhythms accounting for eighty-five per cent of her output. Mrs Crotty appears to have had many of what she called “the old tunes”, that is, local dance tunes and local variations of widely known melodies. Also, I noted some interesting words from the said Companion to Irish Traditional Music. In discussing the concertina repertoire from Mrs Crotty’s part of the country, we are told that, “Because of the influx of travelling teachers like George Whelan from Kerry, the music of the area was linked to the polka and slide repertoires of Kerry and West Limerick”. But there is just one polka on the disc, and no slides. There is also precious little in the way of any local melodies, most of the items being fairly standard settings of fairly standard tunes. The impression one forms is that Mrs Crotty ended up mothballing many of the tunes she had played in her youth out of a desire to accommodate other musicians.

The record also contains an English language version of the Gaelic song, An Droighneán Donn (The Blackthorn). I am sorry to have to report that the vigour and passion of her concertina playing is not repeated in her singing of this song. As the notes point out, she was old and in ill-health, and her voice sounds weak and feeble. However, while I can accept this as the contribution of somebody past their prime, I am puzzled by the air. It is clearly of the An Droighneán Donn4 family, but it is simpler than most other versions, and has little of the grandeur commonly associated with Gaelic melody. Indeed, some features of Mrs Crotty’s tune make me wonder if it has not at one time been badly transcribed - perhaps by some Victorian antiquarian working in accordance with contemporary taste - before finding its way back into the tradition

In his book of translations of Gaelic folksongs, Blas Meala, Brian O’Rourke postulates a dependency relationship between verbose Gaelic texts and ornate Gaelic melodies – i.e. the long textual lines, which are so characteristic of Gaelic folksong, require equally long melody lines to support them. He goes on to hypothesise that this relationship does not hold for songs which are expressed through the less complex medium of English. English language songs, it is thought, characteristically have shorter lines and therefore need less complex melodies. I am not wholly convinced by this argument. The language and the music of the Gael are an important part of a conflux of influences, which between them moulded what have come to recognise as Anglo-Irish folksong. In fact, as O’Rourke is forced to recognise, many Anglo-Irish songs are on a common footing with the artefacts of Gaeldom, in terms of long melodic and textual lines.

Nevertheless, I find myself wondering whether he had Mrs Crotty’s version of An Droighneán Donn in mind when formulating this theory. Incidentally, Michael Tubridy describes this as one of the ‘major Connaught love songs’, and tells us that “The more common Connaught version” may be found in a book called Cuisle an Cheoil3. I am not familiar with this book and was unable to trace the title in any bibliography. However, the name of the publisher, An Roinn Oideachais (Education Department), makes me wonder if this is a song book for children. If so, then it does not sound the most reliable of sources. In any event, Mr Tubridy would have done well to point readers in the direction of O’Daly or O’Sullivan or O’Rourke or Hyde or Mhic Choisdealbha, all of whom published versions of it. There is some internal evidence that it originated in North Connaught, but the song has been reported from virtually every corner of Gaelic Ireland. There is no such thing as a ‘common Connaught version’.

Unfortunately, the inadequacy of these notes is not confined to an inauspicious reference to an obscure songbook. For one thing, Michael Tubridy’s command of English is less than satisfactory. This is not merely a question of aesthetics, although it did turn the booklet into a tiresome read. More to the point, his style of writing is apt to confuse the reader. For example, in pointing to the lack of decoration in Mrs Crotty’s playing, we read, “She used one method of ornamentation which was common years ago but is not often heard now, which suits the instrument very well, and that is, playing the high part of certain tunes in octaves, rather like what a pair of fiddle players sometimes do”. As a non-concertina player I am not sure whether I understand this. Moreover, I wonder whether the term ornamentation is the right one to use. Ornamentation, as distinct from any other form of decoration, refers specifically to the addition of notes to the melody line. I am not clear how the playing of octaves would qualify under such a definition. In passing, an unornamented style is pretty much what I would expect from someone who is first and foremost a dance musician.

There are still other aspects of the booklet which sadden the scholar within me. For example, most of the tunes are identified by reference to printed collections. Thus, Andy Hehir’s Jig is identified as ONMI 704 which turns out logically to be tune number 704 in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland. However, since most of the settings here do not accord with those of the quoted publications, I fail to grasp the reason for this. In a work of such historical importance, I would have preferred to see RTÉ’s own index numbers, together with the various recording dates and locations. Readers are even left in the dark as to whether this disc encompasses everything Raidió Éireann recorded from Mrs Crotty. I suspect that it does. Thirty-one tunes seems a paltry haul for several recording sessions. However, my own collection, gleaned from long years of taping RTÉ traditional music programmes, yields no more gems than are retailed here. However, a note of clarification would have been in order. Other tantalising bits of information are left out. For instance, we are told that she once privately recorded a double sided 78 disc. A couple of straws in the wind suggest that it was an important event. The cutting of the disc entailed a special journey up to Dublin and she was chauffeured there by a high-ranking member of the cloth, one Monsignor O’Dea. We are not told however, why or when the recording was made, or whether any copies survive, or whether either side is included on this CD. One of them in fact was a duet with Mrs Harrington, and that one we can eliminate by deduction. Mrs Harrington, as earlier remarked, is not one of the musicians ‘guesting’ on this disc.

The biggest let down, though, is the lack of any proper appraisal of Mrs Crotty’s status in the world of traditional music, or any acknowledgement that her standing was in any way unusual. Instead, we find a naive observation that, had she gone to America, she might have ended up making records, just like Michael Coleman, or James Morrison, or John McKenna. This is a most unlikely prospect, for Mrs Crotty was hampered in two respects. She was a woman, and she habitually played single tunes. A man unable to play medleys would have found it very difficult to break into the pre-war recording market. For a woman similarly handicapped, it would have been little short of a miracle.

Discographies of pre-war Irish musicians are neither comprehensive, nor much in evidence. Even if this were otherwise, I doubt that they would identify more than one or two solo female instrumentalists. There are female piano accompanists and there are female céilí band members, but the solo recording artists were invariably men. Male domination of the pre-war 78 industry, by the way, was by no means confined to Irish recordings. Look down the so-called 'race' catalogues of the companies who were recording country blues performers, and you see hardly anything in the way of female names. Graze the white country catalogues of the same companies ... before the women of The Carter Family told the world of the woes of wedlock, and the position is no better. Check out the list of artists of any LP or CD reissue of ethnic 78s and you will find the same thing. Yugoslavia, Poland, Sweden, The Ukraine, Ireland; the overwhelming preponderance is towards men.

The patterns which favoured male recording artists in the New World echoed discriminatory usage as it had existed in the musician’s home countries. To put it another way, custom and practice within music making reproduced models of discrimination against women in the world at large. Why was this, and what factors in our own time have wrought such a change?

The first part of that question may be solved by reading Tim Rice’s marvellous study of Bulgarian music, May it Fill Your Soul5. During fieldwork in Bulgaria, Rice, who is an American ethnomusicologist and not to be confused with the pop song lyricist of the same name, discovered a musical division of labour not unlike that which formerly existed in Ireland. He argues that it arises out of the division of labour within the home, and from the fact that society ascribes to the housewife the twin functions of home making and child rearing. As with Ireland, Bulgarian traditional music was played for dancing, and dance houses were the preserve of single and married men and unmarried women. Under such a status quo, there is little point in teaching your daughter to play an instrument. When she becomes a wife the needle, the sweeping brush, the cooking pot and the cradle will take up all of her time. There will be none left in which to nourish the human spirit in dance, or to nurture the soul with the arts of instrumental music. Therefore, in Bulgaria, it is men who play the musical instruments, whilst women are left to find emotional and artistic outlet in singing. Not surprisingly, there are some great women singers in Bulgaria, for such a regime must have given them plenty to sing about. If we find a similar division in Mrs Crotty’s Ireland, then it must be said that the lines were not as starkly drawn. Rural Ireland had plenty of male singers and one can at least count a few female public musicians among Mrs Crotty’s contemporaries. There was the aforementioned Agnes White of course, and her sister Bridie, and their fellow Ballinakill resident, Lucy Farr, and of course Mrs Harrington. That would not exhaust the list. Even so, it does not add up to a very good deal as far as women were concerned.

Figure 1 The Clare County Branch of CCÉ pictured in 1954. Elizabeth Crotty is in the centre of the picture and Peadar O'Loughlin clutches the banjo.

Improvement in the status of women musicians was chiefly a function of changing attitudes towards women generally. Changing attitudes in turn are attributable to a variety of factors; improved living standards, better education, better communications, etc. Improvement of women’s lot in the sphere of music, however, was due also to changes in traditional music and dancing practices. It followed the decline of house and crossroads venues and their replacement by events which convention regarded as more suitable for mixed attendance. 1951 saw the founding of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, an organisation which places a great deal of emphasis on Irish music as family entertainment. In 1954, the Co. Clare branch of CCÉ was brought into being and Mrs Crotty was elected President. She served in that position for the rest of her life. Curiously enough, the only mention of sex discrimination that I picked up anywhere in the booklet is made in conjunction with CCÉ. We are told that the lack of women entrants to concertina competitions at CCÉ organised fleadhs, was due to the climate of the times, rather than to a lack of women concertina players. This would seem logical. However, if the social climate discouraged women from entering competitions, it is also likely to have been an inhibiting factor, in terms of their taking up instruments in the first place. In Mrs Crotty’s case, however, I’d have thought that her venerable status, as elder musician and County Branch President, would have placed her beyond the ambit of competitions.

I have expressed a fair measure of dissatisfaction with the booklet notes, not because they are particularly inaccurate, but because they are bad history. History does not exist in the retailing of facts, but in the weighing of evidence, and in the drawing of supportable conclusions. This booklet does neither. As a consequence, we are left in the dark, in terms of reaching any real understanding of Mrs Crotty, or of other musicians in her situation. We cannot, as the sociologist C. Wright Mills put it, apply the sociological imagination. That is, the evidence here does not convey any impression of what it must have been like to be a female musician during Mrs Crotty’s time. Apprehension of the medium of Irish music entails an understanding of its importance as a socio/historical phenomenon. We need to perceive the music, not solely as a source of popular entertainment, but as a part of the matrix of people’s lives. We need to see how the practices of music and dance were accommodated by, and reflected the social organisation of rural Ireland.

Yet, such a reservation notwithstanding, this release comes under the heading of 'absolute must have'. Over the past few years RTÉ have released some superb archive material, from some of the most celebrated names ever to have graced the Irish airwaves. The name of Mrs Crotty is no mean addition to a small but splendid catalogue.

Fred McCormick - 12.1.00

Notes:

- Fintan Vallely, ed. The Companion to Irish Traditional Music. 1999. Cork University Press, Cork.

- Brian O’ Rourke, Blas Meala; A sip from the honey pot: Gaelic folksongs with English translations. 1985. Irish Academic Press, Dublin

- Cuisle an Cheoil, 1976, An Roinn Oideachais. No editor indicated.

- Texts of An Droighneán Donn can be found in:

- John O'Daly, Poets and Poetry of Munster, 1849. Publisher unknown.

- Donal O'Sullivan, Songs of the Irish: An anthology of Irish folk music and poetry with English verse translations. 1960, Browne and Nolan, Dublin.

- Brian O'Rourke, Pale Rainbow: An dubh ina bhan; Gaelic folksongs with English translations. 1990, Irish Academic Press, Dublin.

- Douglas Hyde, Love Songs of Connacht. 1969. Irish University Press, Shannon.

- Eibhlín Bean Mhic Choisdealbha, Amráin Muige Seóla: Traditional folksongs from Galway and Mayo. 1990, Cló Iar Chonnachta, Indreabhán.

- Tim Rice, May it Fill Your Soul: Experiencing Bulgarian Music. 1994, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

This review was written by Fred McCormick in 2000 for Musical Traditions – www.mustrad.org.uk.