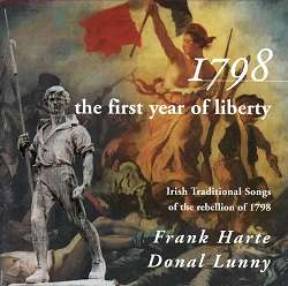

Frank Harte with Donal Lunny

1798: The First Year of Liberty

Hummingbird

HBCD 0014; 68 minutes; 1998

What I wanted to find out more than anything else was; why do people have to suffer? Why was there two acres of land and twenty-five acres of rock? And why was there such a thing as somebody with a thousand acres to run their hounds and horses through the fields and collect their money after them? What did they do to deserve it? I suddenly hated the people who did it, you know, oh the history .........

Joe Heaney

When William, Duke of Cumberland, rode into London, after

subduing the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, he did so to a hero’s welcome.

Among the celebrants was one Georg Friederich Haendel, another idol of elite society

and the protégé of the German Kings of the House of Hanover. Haendel’s

oratorio, The Messiah, had startled the music worlds of London and

Dublin some years earlier. To celebrate their contemporary saviour,

Haendel penned another biblical oratorio, Judas Maccabaeus, which

contains the anthem, Hail the Conquering Hero Comes. The Duke of

Cumberland had just spent several months in the Scottish highlands, butchering

women and children.

I mention this because Frank Harte’s notes to the present CD begin with a headline quote: “Those in power write the history, those who suffer write the songs”. The quote is inaccurate for a number of reasons. First of all, the voices of the lower orders have, at different times and in different ways, leached onto the printed page in sufficient profusion to form a fairly significant library. We do for instance, have some small grasp of what life must have been like for been an Irish migratory labourer, or a shepherd of the English South Downs, or an inhabitant of that bleak and rocky island off the coast of County Kerry, the name of which imperious Albion rendered into English as the Great Blasket.[1] Secondly, the powerful do not always content themselves with anthems of oppression. They too have songs, but genteel creations such as Silent Worship, or Drink to me Only With Thine Eyes, cannot match the fury of a well-aimed street ballad. Finally, Frank Harte has accompanied this CD with an estimable history of the 1798 rebellion. I doubt that Frank would count himself anywhere but among the sufferers.

Before we delve into the history, I would like to compliment all concerned on a most commendable production. The booklet, as well as containing a concise account of the rising, has biographies of all the leaders of the 1798 rebellion, and a handsome cover illustration. It has a substantial bibliography for those seeking further enlightenment, and it makes a useful complement to the more orthodox histories thereby listed. In fact, it tells us what orthodox histories do not tell us; what those who suffered made of the events of 1798.

Frank’s appraisal of the uprising is necessarily rather brief, but it is even-handed and thorough. It chronicles the events - describes in some detail the reign of martial law and terror imposed even before the rising broke out - and it probes the causes, and promotes thought-provoking parallels with the present. I confess that my knowledge of the minutiae is not equal to the task of detailed examination. However, I did raise an eyebrow over the alleged efficiency of the network of British spies. It is true that the British government made extensive use of spies and that this tactic led to the arrest of the entire Leinster Directory and to the subsequent failure of the uprising in Leinster. Nevertheless, the failure of the British to quell the insurgence in its incipient stages, suggests that the arrest of the Leinster Directory was one of their few successes in that direction.

I raised an eyebrow too, over some of the root causes. Connections are established between the roles of Ulster Americans in the War of Independence and their counterparts back home; there are parallels drawn with revolutionary insurgents on the continent; and there are issues made of the policies of William III and the penal laws, and the effects all these things had in terms of channelling revolutionary opinion. All well and good, for they are all valid reasons. What is missing are the fears and apprehensions of the English authorities. Why did they feel the need to crush the rebellion with such brutality? That may seem an obvious question, for the times themselves were brutal. As Frank’s notes demonstrate, atrocities were committed on both sides - and harsh repression is the way of imperialism and it is the way imperialists have always thought. To the English overlords, Ireland was British by the will of God and, by God, the Irish would suffer if they did not recognise that fact. However, I do not think that is the whole story.

The English had not long lost America, another sovereign colony, with consequent loss of revenue. They would not be in any mood to lose Ireland, with all the tithes and taxes generated from the tenants of Ireland’s great estates. Moreover, the insurgents, in allying themselves with the doctrine of The Rights of Man, effectively and practically allied themselves with England’s mortal enemy. They were traitors in English eyes and, in English eyes, got no more than they deserved. Consider moreover, the strategic implications if Napoleon had managed to ensconce himself, not just to the south of the island of Britain, but was also to gain a foothold on its western flank. There are reasons aplenty then to explain why the English ruling classes crushed the rebellious Irish in such rivers of blood that their lordships could have swum in it. Yet even these factors do not tell the entire story. There were happenings in England which made repression of the Irish an absolute necessity.

I met murder on

the way - he had a mask like Castlereagh -

Very smooth he looked, yet grim; seven blood-hounds followed him.

From - Shelley - The Mask of Anarchy.

Like Ireland, England was an unfree and unfair society. It too was a hot bed of intrigue and it too was crawling with spies. Like the Irish, many English people looked to the events of the continent for inspiration and salvation. Like the Irish, many English people plotted intrigue and overthrow. Rebellions beget rebellions. If the rebellions of France and America were succour to the downtrodden English, how much more fuel would have been placed on the fire, had a successful revolution taken place on their doorstep? How much more trigger happy would the authorities have been? Even when revolution in Ireland had been successfully aborted, and even when the French had been defeated, the English authorities dared not feel safe in their beds. Two decades after the suppression of Ireland, and four years after the defeat of Napoleon, a peaceful demonstration at Peters Fields in Manchester was sabred by ranks of yeoman cavalry, who incidentally were organised along similar lines to those which had wrought such havoc in Ireland. The only crime of these people was that they had assembled to demand the basic and fundamental rights of citizenship of the country of their birth, a country to which they had paid tithes and taxes, and which many had defended with their blood. The most appalling part of that debacle is that the government of England, on behalf of the Prince Regent son of an "old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king", to quote Shelley again, thanked the magistrates and yeomanry officers for their actions on that day. They were thanked just as the Duke of Cumberland had been thanked, and just as the officers who suppressed the rebellion of 1798 had been thanked.

Why bother with history? Why drag these events up? Why do we trouble to acknowledge a record of happenings which took place two centuries ago, in a different world, with different moral values, the memories of which can only inflame present opinion? Well, the trail of slaughter, which stretches from the Scottish highlands, to the plains of Kildare, to the massacre of Peterloo, does not stop with Peterloo and it is not confined to the landmasses of Ireland and Britain. It is a function of oppression. It is a function of that part of human social relations that labels and condemns people on the grounds ‘they’ are different to ‘us’. It is a trail well known to historians, for they are the ones who write the history. It is not a trail known to the mass of ordinary, decent working people, and therein lies the crux of the problem. The events of 1798, along with all the other significant dates in Ireland’s long and troubled history, continue to reverberate into the present era. They are the forces which shaped and defined the system of power relations within Ulster and they are the root cause of the grossly unequal and grossly unfair systems of anti-Catholic discrimination, which became written into the laws and customs of a sovereign British territory.

Those events defined the political geography of that province. They ignited the present conflict there, and the ordinary people of England, Wales and Scotland do not know why. Because they do not know of any rational explanation for the bombings and shootings and punishment beatings, they assume there is none. What they know is what they were taught, and they were taught of the benevolence of Britannia, and of an altruistic all powerful white ruler, whose guiding presence ensured peace and happiness among her many thankful subjects. Those in power do not simply write the history. They censor it. The fact that the ruling classes so effectively defined the field of vision of those beneath them has defined and distorted English understanding of the role of Britain in Ulster. That is why these songs are important. They are uncensored - and so are their singers.

Many years ago I was told, with all the authority of one who thinks he knows,

that Frank Harte’s stentorian singing style is that of a street singer.

How firmly this contention can be supported I do not know. With virtually

the sole exception of Margaret Barry, we have very little knowledge of what

Irish street singers sounded like. Nevertheless, Frank’s forte is the

kind of ballad you would have heard bellowed the length of the street and his

manner of delivery fully reflected this. Unfortunately, life is full of

downsides. What

we gained in conviction, we lost in subtlety. Over the years, however,

his style has mellowed and it is interesting to contrast his present

interpretation of Dunlavin Green with the way he sang it for Topic

Records a quarter century ago. Where the earlier recording cleaved to the

melodramatic, the present one is a model of understatement and

accusation. I listen to the unfolding of this dreadful massacre and it is

like watching a film of the aftermath of battle. It is like reading one

of the war poems of Wilfred Owen.

It is not the only song to be so treated. Well do I remember the ballad groups who used to parade Henry Joy as though it were an Irish Hail The Conquering Hero; a song of riot and rebellion to trounce the bloody Brits with; a song to exacerbate the causes of conflict; never a song to try and understand the hate that grows in the hearts of men, or still less how we may use songs like Henry Joy to overcome our fear and loathing of those of our fellow human creatures who hold different religious views, or speak a different language, or wear a different coloured skin. It is a pity those ballad groups never paused to take cognisance of the words, for the biblical connotations are extremely striking. A fisherman casts his nets aside to become a disciple of Henry Joy, and he ends up seeing his saviour martyred. This is not a song for tub-thumping. It is a song for quiet reflection and sober celebration. Like Dunlavin Green, it is the very understatement of Frank’s performance which makes it so striking.

Jingoism and bigotry, as those ballad groups were wont to demonstrate, are by no means the preserve of the oppressor. I do not know whether the nationalists of 1798 created any ballads which could be deemed jingoistic or bigoted, and I certainly cannot think of any. On this disc, there is the infamous loyalist riposte, Croppies Lie Down, with its bloodthirstily ironic celebration of the slaughter of ‘bloodthirsty croppies’. There is also the wonderfully inordinate Father Murphy, which tells the same story from the nationalist standpoint. Otherwise, most of the songs focus their energies in celebration of the nationalist leaders. Wolfe Tone is commemorated, so are Henry Munro and Bagnal Harvey, while By Memory Inspired provides us with a roll-call of the names of nationalist leaders of the period. The street ballad, Roddy McCorley, is included, although the notes fail to clarify his role in the conflict. Was he a leader of the insurrection, or was his martyrdom, like that of Kevin Barry, more symbolic? With Roddy McCorley as a possible exception, there are only two songs which celebrate the foot soldiers. There is the famous Croppy Boy which Frank locates, not as many people sing it in Dungannon, Tyrone, but more correctly in Duncannon, Wexford. There is also Robert Dwyer Joyce’s song, The Wind that Shakes the Barley. The fact that so many of these songs hinge around a small circle of leaders highlights a problem which makes me want to shun all wars, no matter how just the cause. In all wars, the greatest losers are the ones whom history forgot. They are the ones who gave their lives and got nothing in return, save the anonymity of the tomb.

Of the songs marshalled here, several sound too polite to have lived on the street. Of these two appear not to have entered folk tradition. They are Bodenstown Churchyard, a celebration of Wolfe Tone by Thomas Davis, and By Memory Inspired. The latter is an anonymous creation which is probably contemporaneous with Davis, and sounds much the sort of thing he would have written. Of the other two, The Wind That Shakes the Barley has been seldom reported by folk song collectors and Steve Roud’s voluminous Folk Song Index gives just two sources; Sarah Makem from Keady, Armagh, and Nellie Walsh of Wexford. However, the fact that these two ladies were from opposite ends of the country may tell us something about the song’s distribution. It may also tell us something about the preconceptions of folksong collectors, regarding what is and is not collectable. The song which particularly interested me however was Henry Joy McCracken, a different composition to the Henry Joy discussed above. Like the Joyce creation, this is a literary song which found its way into folk tradition. In this case, however, a measure of confusion exists over the authorship. Frank gives P J MacCall as the writer and this is a fairly common ascription[2]. However, I have elsewhere seen the song attributed to William Drennan, one of the Ulster leaders of ‘98, and I would have thought Drennan the more likely candidate. First of all, MacCall was a Wexford man. He is not likely to have identified himself as closely with the Ulster uprising, as with happenings in his own part of the world. Secondly, to my ears at any rate, it does not sound like a MacCall composition. I may be doing him an injustice, but MacCall was famed for spirited, rousing compositions; songs like Boolavogue and Kelly, the Boy from Killann which, for all their patriotic declamation, never quite lost the starch of the drawing room. Henry Joy McCracken is a tender love song. It takes for its subject the intimate sorrow of two human beings, caught in the inexorability of an event which is greater and more significant than either of them; and it is written in an altogether less starchy manner.

On hearing By Memory Inspired, I was interested to note the similarity between its melody and that of the English North Country Maid. It is not the only Irish nationalist song to use an English air. In fact I sometimes lie in bed at night wondering if the maker of Ireland Boys Hurrah (not on this disc) realised he had set it to the tune of an English folk carol; The Seven Joys of Mary. Nor are these two the only airs which keep me short of sweet repose. Bagnal Harvey’s Farewell was, we are told, always treated as a recitation, until one Tommy Mallon fitted the present air to it. I am not sure whether Tommy Mallon claims authorship and I have no wish to dispute the matter, but I detect phrases in the melody which appear to link it to a substantial family of Gaelic airs. This family stretches at least from Waterford to Conamara, and its best known member is probably that of the drowning ballad Liam Ó Raghallaigh. The fitting out of Bagnal Harvey with this melody then may constitute an unconscious irony. Many years ago A L Lloyd identified a huge corpus of melodies, which are related to this Gaelic tune family, and which he claimed stretches from East Anglia up to Scotland and across to Wales[3]. In Ulster, it embraces The Star of the County Down and that famous ballad of thwarted piracy, Captain Coulson. In the Southern Appalachian Mountains of the USA it is the melody of a song called Little Maggie, which Bert claimed as the forerunner of the more famous Darling Corey[4]. Some of our most 'English' folk melodies are bound up in this chain and they include Brigg Fair, Dives and Lazarus and that fine version of John Barleycorn which Shepherd Haden of Bampton, Oxfordshire, used to sing. Bert wasn’t prepared to hang far enough out on a limb to suggest Gaelic Ireland as the most likely origin of the corpus. I can only say that I have my hunches. Wherever it started from however, is not the issue. The number of cultural boundaries which the Dives and Lazarus/Liam Ó Raghallaigh family has crossed, and the huge variety of forms into which it has been wrought, demonstrate that in music as much as anything else, nationalism and ethnic identity are concepts of the imagination. The various races of mankind have far more to unite them than to separate them.

Special mention must be made of Donal Lunny’s fine and subtle accompaniments and of an unobtrusive bodhran which creeps in here and there. I am not terribly well disposed to those populist ends of the Irish music spectrum which Lunny represents, and I cannot say that I have listened very closely to his music. However, his performance here is quite exemplary and he does what every good accompanist should do. He allows the singer to tell the song and, where he has anything to say, it is absolutely in accordance with the mood which the singer establishes. To some extent, his presence here reminds me of the way that certain blues singers use the guitar or harmonica as a second voice. On Dunlavin Green, his bouzouki - I presume that is what he is playing, for the notes don’t say - tolls like a funeral bell. On the Shan Van Vocht the instrument picks up the lively rhythm of the song and continually pushes it forward. On Henry Joy, the quiet, measured dignity of the words and vocal are matched by the quiet dignity of the accompaniment.

There are one or two songs which step outside the immediate arena of 1798. Their inclusion is justified however, for they are redolent of the times from which they spring. The Bold Belfast Shoemaker, better known to English listeners as The Rambling Royal, is a song of desertion in which the protagonist joins up with Father Murphy. Likewise, The Wheels of the World is a panorama of social and economic events of the period. It uses the metaphor of fabric spinning for political activity and libertarian strife. With a few changes of subject, it could have been created in an English mill town of the period. In fact it is an unusual song to find in Ireland, being the product of an Irish industrialism, which was itself largely stifled by the failure of 1798, and by the subsequent Act of Union, and the incorporation of Ireland into the United Kingdom. This poses a curious question, for the revolution was largely inspired by middle class Presbyterians, whose aspirations towards upward social mobility had been thwarted by their dissenter beliefs. That is a scenario familiar to English historians, where dissenters were likewise discriminated against, and where they channelled their energies into industrialisation. I am moved to ask then, if the revolution had succeeded and if capitalism had been allowed free rein within Ireland, how many more songs would there have been with messages like The Wheels of the World? To what extent would class warfare have replaced nationalistic strife, and how different a country would Ireland be now?

Thus far, thus good. We have a commendable release which sheds a lot of

light on popular attitudes of the period and which offers an avenue of

explanation as to why those attitudes have endured. What you make of the

songs - whether you see them as the products of lackeys of war or of guardians

of peace - depends on who you are and where you are coming from. For me,

if they are listened to properly, they fall very strongly into the latter

camp. I cannot believe in any solution to the present crisis which does

not entail peace and justice on all sides. Peace and justice are

incompatible with ignorance and the only thing we have to fear from history is

ignorance of history and of the myths and prejudices which arise in its

place. It should be sufficient then for me to say, go buy this record and

play it to everyone who thinks the trouble in Northern Ireland boils down to a

bunch of thick Micks throwing bombs at each other. But it is not that

simple, because the seeds of conflict and sectarian strife are not peculiar to

Ireland. They exist everywhere.

Part two of Mister Haendel’s splendid oratorio contains a curious question; "Why do the nations so furiously rage against each other?" I would far rather that Haendel be remembered for the composition of such an intensely moving and profoundly human work as The Messiah, than for a furious anthem written in the revelry of near genocide. But the trouble is that his biblical question has yet to be resolved. The nations will continue to rage against each other as long as one person is willing to profit from another person’s misery, because oppression and exploitation and discrimination are the very things which propel nations into states of rage. Let me state my feelings on this point completely and without equivocation. We need to distinguish people by their nation, or their ethnicity, or their religion, or their culture, or by any other characteristic which states their place within the ambit of humanity. That is because, in an increasingly cosmopolitan world, they are the things which give identity and meaning to the existence of each and every one of us. What propels the world into states of chaos is not the recognition of people as British or Irish, or as Catholics, or Protestants, or Dissenters, or Blacks, or Jews, or Hindus, or Muslims. It is the failure to recognise that, beneath the skin, beneath the robes of religious practice, beneath the myriad cultural forms which exist around the globe, we are fundamentally one and the same; species generis.

This has been an extremely difficult review to write ... not because of the history, but because of the present. This celebration of the bloody events of 1798 is a timely reminder of just how far we haven’t come in the last two hundred years. In the week prior to this review being composed, the conflict of Kosovo threatened to erupt into pan-Balkan war, and to turn the mass murder of the ethnic Albanians into outright genocide; that wonderful humanitarian, Margaret Thatcher, publicly thanked the butcher of Chile, General Pinochet, for the help he gave ‘us’ during the Falklands war; and the Irish peace process stalled yet again, over the question of nationalist retention of arms. Cruelty, harshness, bigotry are by no means the sole preserve of British imperialism. They are endemic wherever tyranny is endemic - and wherever people are bound to its yoke, they use song as a weapon of struggle. Frank Harte caps that quote about the sufferers making the songs by remarking that we have an awful lot of songs. We do indeed - worldwide!

Notes:

1. For migratory labourers see:

Children of the Dead End. Patrick MacGill, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1914

Come Day, Go Day, God Send Sunday. John Maguire (Robin Morton, ed). RKP, London 1973;

Spalpeens and Tattie Howkers. Anne O'Dowd, Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1991.

For news of shepherds of Southern England see:

A Shepherd's Life. W H Hudson, Methuen, London, 1920.

The Downland Shepherds. Barclay Wills, (Shaun Payne, Richard Pailthorpe, eds). Alan Sutton, Gloucester, 1989.

Over the years a substantial number of publications have poured out of the Blasket Islands. The major works are:

Twenty Years A-Growing. Maurice O'Sullivan (Moya Llewelyn Davies, translator). Oxford UP, London, 1953.

An Old Woman's Reflections. Peig Sayers (Seamus Ennis, translator) Oxford UP, London, 1962.

Peig. Peig Sayers (Bryan MacMahon, translator), Talbot Press, Dublin, 1974.

The Islandman. Tomás Ó Crohan (Robin Flower, translator) Oxford UP, London, 1951.

2. Frank's notes do not say where he learnt this fine song. However, I suspect that, as with many other items in his repertoire, his is the version which was published by Colm O'Lochlainn (Irish Street Ballads. Three Candles Press. Dublin 1939). O'Lochlainn ascribes the song to MacCall, as does Maurice Leyden (Belfast: City of Song. Brandon, Dingle, 1989). It may be however, that Leyden is simply repeating O'Lochlainn's claim. Patrick Galvin (Irish Songs of Resistance. Oak, New York, 1962) is one of those who cites William Drennan. In fairness, and in spite of my inclination towards Drennan, I have not found always Galvin's book an entirely reliable source of information.

3. Folksong in England. A L Lloyd. Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1967.

4. Topic 12TS 336. The Watson Family Tradition. Lloyd identifies Little Maggie as the progenitor of Darling Corey in the sleeve notes. Identification of the melody as part of the Dives and Lazarus family is based on aural impressions on my part.

This review by Fred McCormick was written originally for Musical Traditions in 1999.

For more information about Hummingbird Records visit www.hummingbirdrecords.com.