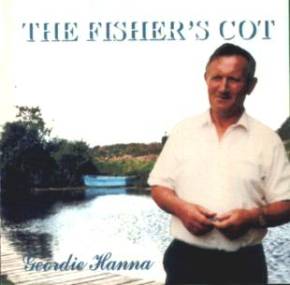

Geordie Hanna

The Fisher’s Cot

The Hanna Family – no number; 70 minutes; 2002

Geordie Hanna was one of

those singers whose scant recorded output belied the enduring influence of his

singing. Prior to the release of The Fisher’s Cot, the only available

recordings were the 1978 Topic LP On the Shores of Lough Neagh (which

has never been reissued in CD format and also features his sister Sarah Anne

O’Neill) and a cassette (I think) titled Geordie Hanna Sings, released by

the Eagrán label, though he does also feature on several compilations. Thus, The

Fisher’s Cot, released fifteen years after his tragic death in 1987 is a

thoroughly welcome addition to the recorded archives of Northern song.

The Fisher’s Cot is very much a homemade recording, catching Geordie

singing, recounting tales and being interviewed by Séamus Mac Mathúna on

cassette tapes and the only enhancement made to the original recordings has

been to adjust the sound level. Intriguingly, for those with a knowledge of

Northern Irish history, most of the recordings were made in the house of his

neighbours Bernadette and Michael McAliskey. Bernadette (née Devlin) was a

leading light in the Civil Rights Movement which rose up in the late 1960s

seeking to eradicate political and social inequalities in Northern Ireland.

Famously, she was elected the UK’s youngest ever MP in 1969 and, notoriously,

she assaulted Reginald Maudling, the British Home Secretary, in the House of

Commons in 1972 shortly after the iniquitous events of Bloody Sunday. She did

not stand for re-election in 1974 and, the following year, co-founded the Irish

Republican Socialist Party in 1975. Heavily involved in support for the 1981

IRA hunger strikes, she and Michael survived a UDA attempted assassination that

year.

Bernadette provides a

tribute to Geordie in the liner notes and writes in warm remembrance of her

late friend, particularly about his musical gifts:

Geordie’s reputation as one of the finest traditional singers of our time is beyond dispute. The wealth of the knowledge he possessed is well known, yet he never forgot how he came by a song, he never resented passing it on from him to whoever would use it on again. “He can sing none the best” was as much criticism as the least musical rendering would get from Geordie. I thought it was music to hear him talking. The way he used language was a gift in itself. And it was a gift he never abused. Geordie could tell you yarns, relate everyday events with a phrase or saying that was never said before and nobody could repeat to the same effect.

The closing sentence of that

paragraph is worth bearing in mind when listening to Geordie’s singing style.

Ron Kavana has referred to this as “the most gentle and seductive style of

traditional singing I have ever recorded”[1]

while John Moulden put his finger exactly on the button by describing how the

effectiveness of his singing derived from his “breaking up of the tune and

words into short phrases delivered with great force”[2].

Fintan Vallely has also remarked on Geordie’s “memorably intense engagement

with the actual songs themselves – their subjects, their stories, their

personalities and action. For him they were full of information and mystery.”[3]

Such eloquent unanimity from

such disparate sources cannot possibly be ignored and the sheer length of The

Fisher’s Cot and the breadth of its contents offer ample scope for

exploring the subtleties of the Hanna repertoire. On the evidence of the

nineteen songs collected here, that repertoire was expansive and drew upon

songs learnt both locally and on his and Sarah Anne’s travels to festivals

around Ireland. It encompassed songs known throughout Ireland and further

afield (Paddy’s Green Shamrock Shore, Green Fields of America, The

Flower of Street Strabane) alongside less familiar material learnt from

sources as varied as Cathal McConnell (The Shores of Lough Bran) and the

Keane sisters (The Month of January). Most importantly, however, it was

firmly rooted in the songs of his locality (the countryside around his

birthplace of Derrytresk on the Tyrone shore of Lough Neagh).

So, On Yonder Hill

came from his father Joe, while The Tidy Thatch Cottage, Erin’s Lovely Home

and The Lisburn Lasses were learnt from Jimmy Robinson from Maghery. Two

songs, Brocagh Brae and The Emigrant derived from the pen of John

Canavan from Ardboe, a place whose praises Geordie sings on Old Arboe,

learnt from his neighbour Dan McCann (though said eulogy fails to mention the

mayflies that plague the area in Spring!).

It is an enthralling

collection and the impact of Geordie’s singing is readily accessible despite

the presence of tape hiss and the occasional background noise. More to the

point, it thoroughly emphasizes the quiet certainty, the overriding intimacy of

Geordie’s singing and, unquestionably, merits its place in any song lover’s

collection.

This is an original review by Geoff Wallis.

Unfortunately, the liner does not

give details of a contact website or email address, though Claddagh had copies of the CD when I last

visited Dublin. Should tracking down a copy of the CD prove difficult the liner

includes a contact telephone number – please email for details.