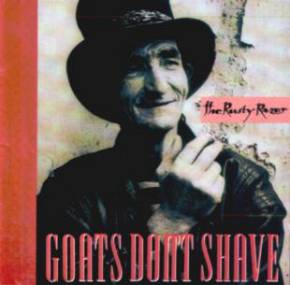

Goats Don’t Shave

The Rusty Razor

Cooking Vinyl COOK

CD 074; 46 minutes; 1992

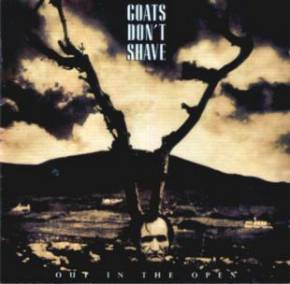

Out in the Open

Cooking Vinyl COOK

CD 075; 41minutes; 1994

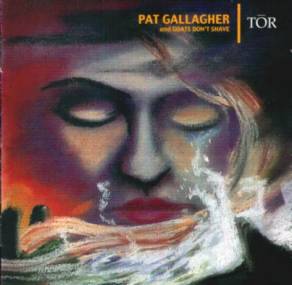

Pat Gallagher and Goats Don’t Shave

Tór

Cooking Vinyl COOK

CD 147; 48 minutes; 1998

Despite all their success

in the early 1990s Goats Don’t Shave were in many ways the ultimate local band.

They might have played the Glastonbury festival and the Finsbury Park Fleadh

and been voted Best Band of 1993 by the influential London listings magazine Time

Out, but, deep down, the band never really left their home town of Dungloe

in County Donegal. Some critics carped that the Goats were hanging on the tails

of The Waterboys and, indeed there are some similarities in their approach, but

the Donegal element was ever-present in the Goats’ music whether it was simply

the subject of Pat Gallagher’s songs, such as Las Vegas (In the Hills of

Donegal) or the instrumental components provided by the likes of fiddler

Jason Philbin (who is, after all, Neillidh Boyle’s grandson) or the

effervescent whistling of Declan Quinn. Others saw the band as a kind of

northwest frontier version of The Pogues due in part to the Goats occasional

ventures into head-down-no-nonsense renditions of reels (powered by Michael

Gallagher’s drums), but, really, that’s where the similarities began and ended.

Formed around 1988, the

Goats initial success came with their single Let the World Keep on Turning,

which subsequently became the opening track on their debut album, The Rusty

Razor. In typically self-effacing fashion the band credited all the members

of their road crew individually and the additional musicians featured on the

album while forgetting to include their own names. All we knew was that Pat

Gallagher had written everything and that their list of acknowledgments

included several pubs in Dungloe, a well-known Annagry restaurateur, one of

Ireland’s sporting heroes (the goalkeeper Packie Bonner, from nearby

Burtonport) and, of course, Mickie (Béag) Gallagher, described as their

“ex-manager” and posing proudly with fag in hand on the cover. I was later to

discover that, for a time, Mickie was banned from every pub in Dungloe, but

that’s another story, although the landlady at Beedy’s Bar told me he was a

lovely man when he was sober.

Apart from the Goats’

instrumental prowess, the most prominent feature of The Rusty Razor was

unquestionably the sheer strength of Pat Gallagher’s song-writing skills. The

most moving song on the album was The Evictions, where Pat takes the

standard ballad format a step further in recounting the notorious events of

April 1861 at Derryveagh when Gilbert Adair kicked all of his tenants off his

land, forcing the majority into penury. Contrastingly, Mary Mary is a

rousing satire on Dungloe’s Mary from Dungloe festival, featuring some

bluegrass banjo and fiddle from Pat and Jason.

Seen a German girl with a backpack that was bigger than a caravan

Who emptied pints of Guinness twice as fast as any man.

There was reels and jigs and Celtic rigs and smoke from Philbin’s bow,

And I cursed the plastic glasses at the Mary from Dungloe.

Daniel O’Donnell’s views

on the song (which concludes with the sound of a sheep baaing) have never been

recorded.

One facet of the Goats’

artistry was to create wonderfully memorable hooks on which to hang a song,

often, as on What She Means to Me (not by any means the best song on the

album), drawing directly from traditional music. However, Gallagher was also

adept at creating sing-along songs in the best tradition of The Saw Doctors (Crooked

Jack is one of his best examples). However, the Goats were never averse to

a little controversy, as the album’s closing track, When You’re Dead (You’re

Great), amply illustrates, commenting sharply on how those criticized

during their lives are often eulogised at their own funerals.

By the time of 1994’s Out

in the Open, whose cover portrays Mickie Béag apparently buried up to his

neck and sporting a set of outsized antlers,  the Goats’ heavy touring schedule had certainly

honed their performance. All the songs were again composed by Pat Gallagher,

but this time were generally characterized by introspection. Sure, there was

always Arranmore, but even that song’s apparent boisterousness becomes

an elegy to the fallen:

the Goats’ heavy touring schedule had certainly

honed their performance. All the songs were again composed by Pat Gallagher,

but this time were generally characterized by introspection. Sure, there was

always Arranmore, but even that song’s apparent boisterousness becomes

an elegy to the fallen:

There was Early and O’Donnell, Gallagher and Boyle,

Doherty and Sweeney, Bonner , Cox and Coyle.

They called them the Tunnel Tigers,

One could do the work of four

And proud they spoke the name Arranmore.

The bottle got O’Donnell,

A falling rock flattened Sweeney’s head.

I haven’t worked in seven years.

Now Sally’s gone and so’s me bloody legs.

Whatever lies before me, win or lose, there’s one thing I know,

I’ll be in a box next time I go below.

Indeed, by the end of his

tale, the song’s narrator curses “the day I left Arranmore”.

Songs such as Last

Call for Help, She’s Leaving and War show Gallagher’s heart

firmly sported on his sleeve, but there remained plenty of room for his cutting

edge too. Let It Go is a formidable attack on bigotry against Travellers

while Children of the Highways, despite its bouncy tune, recounts

the hopelessness of the lives of the young unemployed (remember, this was

before the emergence of the Celtic Tiger).

Still, there’s hope too,

as expressed in the love song, Rose Street (which also possesses the

album’s catchiest riff), but the overriding impression, reinforced by the

album’s closing track, Lock It In (a bitter attack on men who physically

abuse their partners) is of a songwriter willing to face up to many of

Ireland’s most sacrosanct taboos and pull no punches in doing so.

Retrospectively, it seems

no surprise that Goats Don’t Shave began an extensive sabbatical in 1995 (one

that remains in force, despite occasional reformations for the Mary from

Dungloe festival). Though their live performances continued to enthral,

they bore an element of world-weariness and it seemed, from this critic’s

perspective, that the candle was in danger of extinguishment.

It wasn’t until 1998 that

Pat Gallagher re-emerged. He’d move to Bunbeg and had recently become a father.

Tór was recorded up in the hills above Crolly, in a splendid house on

the side of Cnoc na Farragh mountain. Though co-credited, in a smaller font, to

Goats Don’t Shave, the album actually featured musicians from the Bunbeg and

Rosses area, including the fiddler Stephen Campbell, the pianist Hugh (Húdaí

Béag) Gallagher and Séamus McGurrin on banjo. Also featured was the house’s

owner, Éamonn Jordan on concertina and in the role of “chief stoker” (of a fire

which has warmed this reviewer on many an occasion!).

Tór reveals a man exploring the joys of

fatherhood (Sarah), examining his past addictions to booze and fags (Killing

Me), challenging personal boundaries (These Walls) and the

loneliness and guilt felt by orphans (Song for Pat). Musically, the

album bears little connection to the Goats’ two releases and simplicity seems

to be the byword here. Superhero, for instance, relies solely on Pat’s

guitar, the odd drone and a closing few rolls on the concertina.

Tór reveals a man exploring the joys of

fatherhood (Sarah), examining his past addictions to booze and fags (Killing

Me), challenging personal boundaries (These Walls) and the

loneliness and guilt felt by orphans (Song for Pat). Musically, the

album bears little connection to the Goats’ two releases and simplicity seems

to be the byword here. Superhero, for instance, relies solely on Pat’s

guitar, the odd drone and a closing few rolls on the concertina.

Yet Tór’s

strengths lie in Gallagher’s ability to utilize powerful imagery to evoke a

range of emotions from the listener, even when employing other’s words, as in A

Returning Islander, which draws upon Father Diarmuid O’Péicin’s book on

Tory Island, Islanders. And that, five years on, remains the last

offering from Pat Gallagher and Goats Don’t Shave (in whatever guise).

“OK”, some might say,

“but why waste your time writing about a band which was briefly popular and few

now remember?” The answer is straightforward. Whenever Ireland’s musical past

is discussed and the subject of those bands which crossed boundaries is raised

it’s The Waterboys, The Pogues and, to some extent, the early incarnation of

The Saw Doctors which gain all the plaudits. Somehow, Goats Don’t Shave have

been erased from the equation of collective memory. It might be because the

band’s albums were released by a relatively small label (although not a single

CD has ever been deleted since release), for Cooking Vinyl has always lacked

the resources to match its major-label rivals. The more likely verdict is that

Goats Don’t Shave simply had their moment of fame and chose not to capitalize

upon it.

Some might argue that the

Goats’ status reflects the still extant view of County Donegal as a backwater,

but Altan continue to thrive and Clannad’s albums from the 1980s are in the

process of being reissued in remastered format.

Ultimately, the only

answer is to buy a copy of The Rusty Razor, stick it on the stereo and

simply enjoy the best band ever to come from Dungloe!

This is an

original essay by Geoff Wallis.