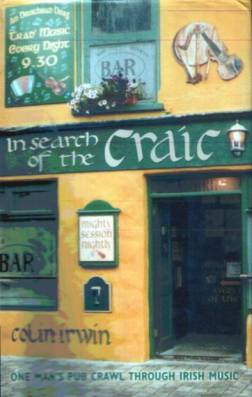

In Search of the Craic

Colin Irwin

Andre Deutsch; hardback; 2003; 256 pages

Recently,

Ireland has offered fertile ground for comedic travel writing – think of McCarthy’s Bar and Round

Ireland with a Fridge, for example – and now comes In Search of the

Craic. Written by one of the UK’s foremost musical journalists, Colin

Irwin, a champion of many an Irish band and musician, In Search of the Craic

tries to follow in the footsteps of Pete McCarthy and Tony Hawks and, frankly,

falls flat on its face in attempting to do so.

The book’s

title itself is nonsensical. Since craic is the Irish for “crack”, that

essential combination of good humour and conversation, fuelled by drink and

music, it’s a little like calling a French equivalent In Search of the Joie

de Vivre. Presumably, however, the publishers thought a book entitled In

Search of the Crack might be mistaken for a drug-related odyssey around

inner-city housing estates.

Next, the book

has been appallingly edited and poorly researched. Typographical errors abound,

including numerous misspellings of Irish words, places and personal names. The fada

is noticeable by its almost complete absence and found amongst the many

mistakes are blunders such as: “Sean O’Riada”; “Thomas à Beckett”; the

transformation of the place name An Rinn to the personal name “Ann Rinn”;

“Garnish Island” (it’s Garinish); “Fleadh Ceoil” and “Fleadh Cheoil na

h’Eireann”; “uillean”; “Cairan Bourke”; “Salt Hill” (instead of Salthill);

“Inish Thiar” (instead of Inis Óirr”), “Ballysodare”; and, worst of all,

considering his quest for Tommy Peoples (see below), the repeated confusion of

the fiddler’s birthplace of St Johnston with the Scottish football team St

Johnstone.

There are

also numerous bloopers and some of the worst include a reference to the duo of

“Séamus Begley and Michael Cooney”; the belief that the harper/composer

O’Carolan was “a seventeenth century giant” (when most of his work was written

in the succeeding century); the statement that the IRA hunger striker Bobby

Sands died in Belfast (he died in the Maze prison near Lisburn); the claim that

Pat Clancy’s Tradition Records was “America’s first Irish music label” which

must be news to any descendants of the M & C New Republic Irish Record

Company founded in 1921; and the thoroughly wrong suggestion that Christy Moore

wrote a song called “Joxter Goes to Stuttgart” (it’s actually “Joxer”) about

Ireland’s World Cup victory over England (it was the 1988 European

Championship). These are just a selection from the first few chapters!

All this

might be palatable, if the book was indeed humorous, but Irwin’s tales meander

too much, regurgitate old stories (such as his account of his attempts to

interview the Jamaican reggae singer Peter Tosh which is, of course, very

relevant to this book’s subject!), and are peopled by an excess of Oirish

stereotypes, sometimes veering towards the blatantly offensive, while there is

nothing comic about his repeated demeaning reference to his accompanying

partner as “Mrs Colin”. At times

too, Colin Irwin ventures into an extremely mundane travel-writing style,

making recommendations such as “be warned, there’s a big hike in accommodation

prices when it’s on” and “avoid Killarney at all costs – a plastic Paddy’s paradise” while

advising visitors to head for the equally tourist-swamped Ring of Kerry

instead!

Moreover, he

contrives to avoid many of the best traditional music spots in Ireland while

heading for the most tourist-ridden ones, ignoring Northern Ireland almost

entirely, but the most damning criticism is that Irwin has little more than a

loose grasp of both Ireland’s musical history and the actual nature of its

traditional music. He certainly seems to know very little about how CCÉ is

organised, has modest sense of the nature of the music itself or stylistic

differences between players and areas of the country, and certainly offers

little in the way of explanation for newcomers. Sure, some of his accounts of

festivals and the musicians he knows best (Christy Moore, for example) are well

written and enjoyable, but there tends to be an over-emphasis on the big

figures of the past to the exclusion of those more recently relevant.

Ultimately,

however, In Search of the Craic tests the reader’s patience, not least

in its repeated references to the song The Fields of Athenry and the

seemingly endless quest to track down the fiddler Tommy Peoples (which one

telephone call to the right person might have easily resolved).

The book’s introduction

is entitled “Just What the World Needs: Another Bloody Book about Ireland”.

Exactly.

A much abbreviated version of this review by Geoff Wallis originally

appeared in Songlines – http://www.songlines.co.uk/.