Na Casaidigh/The Cassidys

Na Casaidigh

Philips (Ireland) 6373 017; 42 minutes; 1981 cassette

1691

Gael-Linn CEFCD 154; 43 minutes; 1992

The Cassidys

Skellig Records SCRCD 001; 46 minutes; 1995?

Off to Philadelphia

Skellig Records SCRCD 96002;

53 minutes; 1996

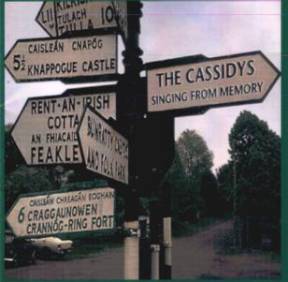

Singing from Memory

Sliced Bread Records SB71180; 45 minutes; 1998

Originally from the Gweedore region of County Donegal, Na Casaidigh seem to

have vanished from the collective memory. Yet, over a period spanning almost

twenty years, this family-based group produced a series of excellent releases,

including one absolute classic. However, attempting to find any of their

material is virtually impossible. None of their original vinyl or cassette

releases of the 1980s, such as their 1981 debut album, Na Casaidigh,  or

its follow-up, Oidhreacht[1],

has ever resurfaced on vinyl, although four tracks from their 1986 LP Fead

an Iolair[2]

were included on the Skellig Records CD The Cassidys. Nevertheless, Na

Casaidigh are an important part of Ireland’s musical heritage and deserve much

wider recognition.

or

its follow-up, Oidhreacht[1],

has ever resurfaced on vinyl, although four tracks from their 1986 LP Fead

an Iolair[2]

were included on the Skellig Records CD The Cassidys. Nevertheless, Na

Casaidigh are an important part of Ireland’s musical heritage and deserve much

wider recognition.

The initial release, picture opposite, featured five brothers (guitarist Feargus, fiddlers Fionntán and Aongus, uilleann piper, whistler and fiddler Odhrán, and keyboards, bouzouki and guitar player Seathrún) alongside their sister Caitrióna on harp. All the family sing on this release, often in unison, although, unlike Altan or Clannad, the songs tend to come from all over Ireland, such as Ailliliú na Gamhna, though the pace of the instrumental tracks, especially, three untitled reels, bears more obvious testament to their Donegal roots. It has to be said that there’s a degree of palpable innocence evident on this recording and a sense that their material and style might have been fashioned to suit contemporary television audiences (they famously appeared at a concert in honour of Ronald Reagan, broadcast live from Dublin Castle).

However, a decade on (and Catrióna having been replaced by

another brother, Ciarán on accordion and bass guitar), the true might of Na

Casaidigh’s musical development was revealed in all its unadulterated glory.

The debut album had included the song, Siúil a Ghrá, recounting the

sadness of a young woman as she bids farewell to her soldier sweetheart who is

sailing away from Ireland following the 1691 Treaty of Limerick to fight with

The Wild Geese in Spain and France. The album 1691, took this one

massive step further, being devoted in its entirety to the Williamite wars of

1689 to 1691. There have been just a few traditional concept albums (the last

being Maurice Lennon’s Brian Boru), but 1691 is unique in

employing solely traditional material, although tunes, such as Lilliburlero,

hardly have a contemporary traditional currency (even for listeners to the

BBC’s World Service![3]).

although tunes, such as Lilliburlero,

hardly have a contemporary traditional currency (even for listeners to the

BBC’s World Service![3]).

Garnering the studio skills of their producer, the guitarist Gerry O’Beirne, Na Casaidigh use the songs and the titles of various tunes (such as The Battle of Aughrim and Sarsfield’s March to provide a parallel musical account of James II’s doomed campaign to save his throne against the European task force and (mainly Northern) Protestant defenders headed by William of Orange[4]. Yet, for the most part, as on the haunting solo piano opening to Aughrim’s Departure, the musicians and their producer opted for simplicity, reinforcing this recording’s sheer impact.

Overall, the effect is stunning, though those with little Irish suffer a diminution as all of the songs (bar Clare’s Dragoons) are sung in Gaelic. Fittingly, the album concludes with Siúil a Ghrá.

Unfortunately, despite the glowing plaudits, Na Casaidigh never made another album for Gael-Linn – one wonders, for instance, what they might have made of the bicentenary of the 1798 Rebellion. Instead their next releases provided rather an odd coupling.

The

first, The Cassidys, appeared on the Austrian label, Skellig Records and

mixed seven newly recorded tracks with four from the aforementioned Fead na

Iolair, produced by P. J. Curtis a decade earlier, and three from 1691,

although the version of Clare’s Dragoons sounds like an out-take[5].

As such, though there’s plenty to merit attention here, the album has the feel

of being cobbled together for the USA market, a point reinforced by the rather

terse liner notes which include one paragraph beginning “Since their first

American appearance in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York....” which goes on to

mention the band being awarded the freedom of the city of Charleston, West

Virginia. In other words, though there’s no concrete evidence for suggesting

so, it’s likely that this album was released to support an American tour (more

of which anon). Strangely, as well, one of the brothers no longer appears on the

liner photo for this or any of their subsequent releases, despite being

credited on each (though it always seems to be Ciarán, by the by).

Nevertheless, and perhaps surprisingly, overall the album actually works,

although here it’s the songs which provide the strong points, especially the

decidedly off Táim in Arrears, which, despite its title, isn’t

macaronic, but recounts the tale of a man caught short, financially, in a pub.

The

first, The Cassidys, appeared on the Austrian label, Skellig Records and

mixed seven newly recorded tracks with four from the aforementioned Fead na

Iolair, produced by P. J. Curtis a decade earlier, and three from 1691,

although the version of Clare’s Dragoons sounds like an out-take[5].

As such, though there’s plenty to merit attention here, the album has the feel

of being cobbled together for the USA market, a point reinforced by the rather

terse liner notes which include one paragraph beginning “Since their first

American appearance in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York....” which goes on to

mention the band being awarded the freedom of the city of Charleston, West

Virginia. In other words, though there’s no concrete evidence for suggesting

so, it’s likely that this album was released to support an American tour (more

of which anon). Strangely, as well, one of the brothers no longer appears on the

liner photo for this or any of their subsequent releases, despite being

credited on each (though it always seems to be Ciarán, by the by).

Nevertheless, and perhaps surprisingly, overall the album actually works,

although here it’s the songs which provide the strong points, especially the

decidedly off Táim in Arrears, which, despite its title, isn’t

macaronic, but recounts the tale of a man caught short, financially, in a pub.

As a result of receiving a tape of the band (though she

doesn’t reveal which one), Dianne Tankle, Concert Coordinator of the

Philadelphia Folksong Society – “They sounded like a combination of The

Chieftains and Mouth Music” – booked Na  Casaidigh,

commencing an annual engagement which included a live recording of their

concert in March, 1995, released the following year as Off to Philadelphia.

The band were joined on stage by “five of Philadelphia’s finest jazz and folk

musicians”, but this reviewer has to apologize profusely for never having heard

of Jay Ansill, Saul Broudy, Robert M. Cohen, Ken Ulansey or Winnie Winston,

several of whom, according to the photographs in the liner, exhibit

idiosyncratic preferences regarding headgear.

Casaidigh,

commencing an annual engagement which included a live recording of their

concert in March, 1995, released the following year as Off to Philadelphia.

The band were joined on stage by “five of Philadelphia’s finest jazz and folk

musicians”, but this reviewer has to apologize profusely for never having heard

of Jay Ansill, Saul Broudy, Robert M. Cohen, Ken Ulansey or Winnie Winston,

several of whom, according to the photographs in the liner, exhibit

idiosyncratic preferences regarding headgear.

As live recordings go, it’s by no means a bad one, though the audience seems nonplussed at certain stages, for instance, wondering when to applaud at the end of Odhrán and Aongus’s whistle/accordion duet on An Binsin Luachra. It’s also questionable whether Bó na Leathadhairce (“The One-Horned Cow”) benefits from the ex-army-beret-clad harmonica warblings of Saul Broudy or, even more misplaced, Ken Ulansey’s soprano saxophone.

It’s best to forgive Na Casaidigh for a recording which seems little more than an aberration, providing a suitable souvenir for those who attended the concert or those who missed it and regretted doing so, especially in the light of what was to come.

Originally released by RTÉ[6]

as Óró na Casaidigh (or ‘Wow, the Cassidys!’, if you’d like a literal

translation), Singing from Memory encapsulates everything that was great

about the Cassidy family and more than a few things which were  a

little askew. Dealing rapidly with the latter, the album features some

alarmingly histrionic electric guitar in places, especially on the track Óró

Sé Do Bheatha ‘bhaile (produced by Steve Cooney), rock drumming, as on Beidh

Aonach Amárach, some occasionally leaden bass-playing and radio sampling,

as on Do Bhíos-sa Lá ibPort Láirge. However, this album’s fourteen

tracks consist of the songs the family learnt in childhood and includes some

utterly startling and, in many ways, unique arrangements.

a

little askew. Dealing rapidly with the latter, the album features some

alarmingly histrionic electric guitar in places, especially on the track Óró

Sé Do Bheatha ‘bhaile (produced by Steve Cooney), rock drumming, as on Beidh

Aonach Amárach, some occasionally leaden bass-playing and radio sampling,

as on Do Bhíos-sa Lá ibPort Láirge. However, this album’s fourteen

tracks consist of the songs the family learnt in childhood and includes some

utterly startling and, in many ways, unique arrangements.

Despite the above misgivings (and the rather odd liner photo, which places the family in East Clare), the album sees the brothers’ vocal talents shining through a variety of somewhat weird arrangements (including a very Baroque An Bhfraca tú mo Shéamusin) and a rendition of Cill Chais whose intro suggest the imminent arrival of Freddie Mercury. It’s undoubtedly an oddity, but, in some ways, none the worse for being so.

That was the very last recording by the band and they seem to have decided to take their final curtain, though Odhrán (to whom I’m indebted for providing some of the information in this article) is still teaching traditional music in Dublin.

This is an original review by Geoff Wallis.