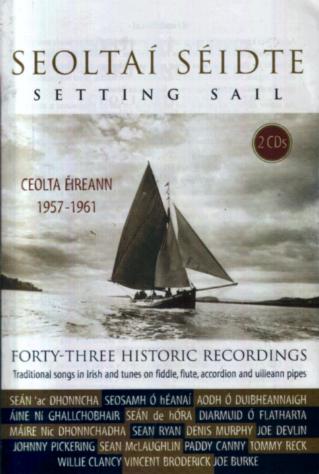

Seoltaí

Séidte/Setting Sail

Gael Linn CEFCD 184; 2CDs; 120 minutes; 2004

Apart from being the oldest record company in Ireland still operating , Gael Linn (sometimes hyphenated) is almost certainly the only one to have evolved from a football pools scheme and Gaelic football at that. The scheme originated in 1953 as an attempt to bolster the activities of An Comhchaidreamh, an organisation founded in the 1930s to promote the Irish language, both in the Gaeltacht areas (where emigration was weakening the language’s hold) and amongst those, in Nicholas Carolan’s words, “trying to lead full lives through the medium of Irish in English-speaking surroundings”[1].

Unlike Littlewoods or Zetters, the Gael Linn system was

based upon subscription with members paying the ‘Irish-language 1/-‘ each week.

This might not seem much, but, by 1959, Gael Linn was paying out more than

£100,000 per year in prizes and investing the rest in such activities as

developing local industries in the Gaeltacht, establishing Foras na Gaeilge (an

organisation running Irish language courses), sponsoring sports competitions

and drama festivals and operating a shopping discounts scheme for pools

members. Added to these, it was producing a weekly newsreel for presentation in

cinemas, making documentary films and producing a weekly programme for

broadcast on Radió Éireann.

This programme began with the intention of promoting the football pools, but it was soon realized that music recordings were needed to maintain the interest of listeners. As there were few recordings of traditional music available, especially of singing in Irish, singers and musicians were recorded on acetate for the programme (by an Englishman, Peter Hunt, who ran a recording studio on St Stephen’s Green). In 1955, however, the idea of Gael Linn issuing its own commercial recordings was first mooted, the intention being “to record every outstanding musician ‘in the old style’ in the country, solo and unaccompanied”[2].

Hunt and his assistant, Gene Martin, were again responsible for the recordings and the first six releases, manufactured by EMI at its Waterford factory, were issued on the 12th December, 1957. Although the heavy 78rpm disc was gradually being phased out and replaced by vinyl elsewhere in the world, there were still plenty of mechanical, wind-up gramophones in the Gaeltacht areas and these six discs were directly aimed at the native Gaelic-speaking population (indeed, Gael Linn internal correspondence actually referred to them as “records of the Gaeltacht”[3]). That the organisation was right to do so is evinced by the fact that, despite costing 5/9 each – a sizeable sum in the 1950s - over a thousand copies of the first disc were sold within eighteen months.

The following year Gael Linn issued its first LP, although this was firmly directed towards a more middle-class audience consisting, as it did, of one side’s worth of Irish airs played by the Radió Éireann Light Orchestra and the other of songs in Irish performed by the tenor Tomás Ó Súilleabháin, accompanied by Seán Ó Riada at the piano.

The next twelve 78s did not appear until October 1960 as well as more middlebrow vinyl EPs and LPs that year. The final two 78s were available in May 1961, by which time the format’s days were strictly numbered. Nevertheless, there were clearly plenty of wind-up gramophones around for copies of the singles that had not been sold out continued to be purchased well into the 1960s. Indeed, it is reckoned that some 15,000 were purchased overall.

Gael Linn, of course, developed its recording activities

considerably, though the pools scheme bit the dust a long while ago. Between

1958 and 2000 the company issued some one hundred and eighty albums, including

many justifiably regarded as classics, although by the beginning of this

century a decision was taken to downsize its musical activities. However,

recently these have been somewhat revived through not only the release of newly

recorded material, but also the reissue of several long-lost vinyl LPs and

other material.

Easily the most important of these is Seoltaí Séidte which compiles all those original twenty 78s for the first time. Those records together comprised forty-three tracks, fifteen of which were reissued on Na Ceirníni 78 1957-60[4], an LP released by Gael Linn in 1979. The rest have remained unavailable since the 1960s, though “several tracks have been published without permission on CDs in the United States in recent years”[5].

The release of Seoltaí Séidte celebrates Gael Linn’s fiftieth anniversary and this reissue project has been conducted in collaboration with the Irish Traditional Music Archive whose director, Nicholas Carolan, has compiled the extensive 96-page booklet accompanying the two CDs, and whose former sound engineer, Harry Bradshaw, had responsibility for remastering. The latter’s task was made immeasurably easier by the fact that, in 1992, Proinsias Ó Conluain (to whom we should be infinitesimally grateful) donated mint copies of all twenty 78s to the Archive.

The two compact discs follow the running order of those recordings and, thus, resolutely reinstate Gael Linn’s original schemata. The A-side of each of those 78s was always devoted to singers from the various Gaeltacht areas singing in Irish, while the B-sides contained instrumental music from the English-speaking areas. Taking the series as a whole, singers from Connemara proved the dominant force – both Seán ‘ac Dhonncha and Seosamh Ó hÉanaí appeared on six of the 78s and Máire Nic Dhonnchadha on two. The remaining six featured two Donegal singers, Aodh Ó Duibheannaigh and Áine Ní Ghallchobhair, on a couple each, and two from west Kerry, Seán de hÓra and Diarmuid Ó Flatharta, on one disc each. It is perhaps surprising that Nioclás Tóibín from the Waterford Gaeltacht was not included (though his absence would be rectified by later 45rpm releases) and that the Muskerry Gaeltacht was not represented. However, this in part reflected the Dublin base of the recording studio. Several of the singers appeared regularly at Gael Linn events in Dublin (indeed, both women actually lived in Dublin), though the two Kerry singers were recorded during a weekend when they had visited the capital for the All-Ireland Football Final.

The choice of the featured instrumentalists also seems to have been deliberately made to reflect different styles, so the fiddlers chosen were Seán Ryan (Tipperary), Denis Murphy (Kerry), Joe Devlin and Johnny Pickering (both Armagh), Seán McLaughlin (Antrim) and Paddy Canny (Clare). The pipers were Willie Clancy from Clare and Tommy Reck from Dublin, while the only flute and accordion players were both Galway men, respectively Vincent Broderick and Joe Burke.

So, for the most part, listening to these CDs is a matter of

aural alternation. Occasionally, the vocalists sang two short songs together,

but otherwise it is a matter of tune following song following tune following

song, etc. Some listeners might find this an irritation, but, as they will

later read, they would be wrong to do so. Those attracted by the high standard

of the singers (and, believe me, they are high indeed) may regard the

instrumental tracks as musical interludes, while lovers of traditional tunes

may take the opposite view. Undoubtedly, however, together they form a

thoroughly impressive collection and it is not difficult to understand how

“Seán ‘ac Dhonncha and Seosamh Ó hÉanaí especially became stars, and the

versions of the songs on the records became widely known”[6].

Quite rightly, Nicholas also points out that the fame of those two singers

might also explain the reason why the Connemara style of singing became

prominent in the general public’s perception.

Whether the same impact can be inferred regarding solo instrumental playing is questionable. Certainly, it is probable that particular tunes (or even sets of tunes) became more widely known as a result of these recordings, though others, such as The Kerry Reel, were already well-known from Michael Coleman’s recording. Several of the musicians, including Paddy Canny, were previously very familiar to radio listeners[7] and others and others would become influential as a result of their appearance on the 78s.

Though CCÉ competitions might have kept the tradition of solo playing alive, albeit in sometimes highly rigorous way, commercial recordings featuring such unaccompanied music became the exception rather than the norm[8]. The coming of the session to Ireland’s pubs had a profound impact on the solo tradition, as did the rise of the group and, especially, the effect of the legions of guitarists and bouzouki players this engendered. Then, additionally, there was the status accorded to a musician through having his or her own accompanist (think of Seán McGuire[9] and Josephine Keegan).

Whatever the case, there is an astonishing array of talent displayed over these two albums. The singing is ever sumptuous and these ears are particularly impressed by Aodh Ó Duibheannaigh’s mellifluous rendition of Geaftaí Bhaile Buí, whose air fully encapsulates the emotions expressed in this love song. Johnny Pickering’s somewhat rough-edged, but ever resonant rendition of Jackson’s Rum Punch which follows seems entirely apposite.

Diarmuid Ó Flatharta’s song An Seanduine (‘The Old Man’) incorporates all the comedy inherent in the tale of a young woman persuaded to marry a much older male[10]. Here’s a sample from the translated lyrics:

If you marry an old man, you’ll marry a useless man, he’ll throw his clothes in front of you on the stairs; coming on to morning he’ll be complaining with feebleness, and late in the afternoon he’ll be playing merrily.

Then there’s Willie Clancy’s gorgeous reading of the air to Na Connerys which seems to blend effortlessly into one of ‘ac Dhonncha’s most acclaimed songs, An Draighneán Donn (clearly, this reviewer has no problem with aural alternation).

All of the fiddlers appear to be on top form, especially Paddy Canny and Denis Murphy, and Vincent Broderick (a much underrated flute player) is captured at the peak of his powers on Down the Broom. It is also a complete pleasure to hear the young Máire Nic Dhonnchadha giving he all on Caisleán Uí Neill[11], though Joe Burke’s merry reading of The Golden Keyboard does seem curiously out of place as its aftermath.

If the sheer quality of these recordings has not yet convinced you of the ineffable worth of this material, let us move on to the packaging. Anyone who has purchased one of Musical Traditions’ own releases will be tickled to discover that a major traditional music label has borrowed our esteemed Mr. Stradling’s presentational innovation. Seoltaí Séidte actually utilizes the DVD case format, although one disc is housed slightly above the other which does mean that one has to remove both to listen to the lower of the two discs so stored.

The inside of the case liner consists of a scan of the front covers of all twenty 78s, although even with magnifying glass in hand it is hard to discern all of the details. In any case, the rear sides of the covers were far more interesting, consisting of photographs of the musicians and singers and the song lyrics, but, sadly, none has been reproduced.

Housed opposite the discs is the aforementioned booklet. Nicholas Carolan’s introductory essay on the establishment of Gael Linn, the recordings and their influence is presented bilingually, with the English version on the left hand page and the Irish opposite. As far as my limited Irish is able to discern, these seem to be literal translations, though I would have to ask Nicholas to discover which was written first. The two accounts do not exactly run in parallel because of the photographs employed. These include: a shot of Gael Linn’s former Grafton Street HQ (including a bizarrely shaped rear-engine car in the foreground); a picture of the renowned Cork hurler, Christy Ring, being filmed for a company documentary; a very young P.J. Hernon (the accordionist from Connemara) perched on his father’s lap while Tomás Cheaite Breathnach dances in a suit which puts new meaning into the words ‘off-the-peg’; a Kerry barrister/businessman sporting a serious Hitler moustache; Peter Hunt operating some very primitive recording equipment; and, an extremely young, slim and shaven Joe Burke playing the accordion while Seán de hÓra searches his (not Joe’s) pockets for a match to light his fag.

Then follows thirteen pages of biographies, all illustrated by monochrome photographs of the subjects. These are brief, and in some cases sketchy (especially that of Áine Ní Ghallcobhair) and provide little more than summaries of the subject’s life and achievements. However, there is one somewhat repetitive and annoying element. This is the repeated reference to the fact that so-and-so “made several other commercial recordings after these” or similar words to that effect. It would have been extremely useful to be provided with such discographical references and the Irish Traditional Music Archive certainly has the resources to provide them. In some cases, of course, such as Seosamh Ó hÉanaí, that information is relatively easy to track down. However, this is not so readily achieved in the case of fiddlers such as Johnny Pickering or Seán McLaughlin and, frankly, the revelation that a “commercial record of Reck’s piping had been issued illegally in the United States before these” is not at all helpful.

The final section provides extensive details of all the songs (lyrics provided in both Irish and English) and the tunes, including their sources and essential information regarding their titles, as some were wrongly described on the original recordings. As one would expect from Nicholas and ITMA, these have all been thoroughly researched, though there is still the occasion when the reader wants to know a little more. For instance, we are told that The Kerry Reel was recorded in New York by “a Kerry fiddle player in 1926 as The Green Fields of Rosbeigh”, but not informed as to the fiddler’s identity.

However, that is a thoroughly miniscule quibble in terms of the sheer eloquence and contemporary relevance of these recordings and the coherence of the package in its entirety.

Seoltaí Séidte resolutely reinforces Gael Linn’s status as a quality traditional music label, thoroughly enhances the status and influence of the singers and musicians who featured on the recordings, reminds us that without the Irish Traditional Music Archive the world would be a much poorer place and, perhaps, above all, is an astonishing testament to Ireland’s musical traditions. Then there’s Seosamh Ó hÉanaí’s wonderful Sadhbh Ní Bhruinneallaigh. Who on Earth could want for more?

This review by Geoff Wallis was originally written for Musical Traditions – www.mustrad.org.uk.

For more information about this and other Gael Linn releases visit www.gael-linn.ie.