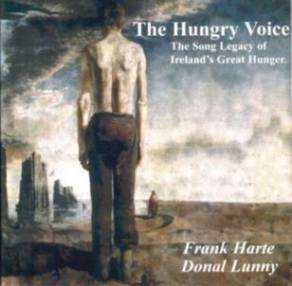

Frank Harte,

Dónal Lunny

The Hungry

Voice: The Song Legacy of Ireland’s Great Hunger

Hummingbird HBCD

0034; 78 minutes; 2004

The Hungry Voice is the third in a series of themed song collections recorded by Frank Harte with the assistance of his regular accompanist Dónal Lunny for Dublin’s Hummingbird Records. The earlier two albums (1798: The First Year of Liberty and My Name is Napoleon Bonaparte) both received extensive and much deserved assessment in previous reviews for Musical Traditions and it would be futile to rehash arguments already available to readers on the Reviews pages.

As the album’s title makes abundantly clear, this time around Frank’s subject is the songs which describe not only the atrocious suffering of the Irish people during the years of the potato blight from 1845 to 1849, but those which also reflected upon the famine’s longer term impact, particularly in terms of the mass emigration which ensued.

Consequently, there are some superficial similarities

between The Hungry Voice and Mick Moloney’s collection, Far from the

Shamrock Shore[1]. Mick’s

purpose was to recount through song the story of emigration to North America,

but there is only a slight overlap in the material he and Frank have selected.

Just three songs (Skibbereen, The Green Fields of America and No

Irish Need Apply) appear on both albums.

In itself that illustrates the sheer wealth of material from which Frank was able to select the seventeen songs which appear on The Hungry Voice. However, the majority of these will be very familiar to anyone with a keen interest in Ireland’s English-language song tradition. Some, such as Rigged Out, are not that well known, but there are others, including The Shamrock Shore and Lone Shanakyle, which have been recorded several times previously. Equally, certain singers have become associated with particular songs, such as Paul Brady with Paddy’s Green Shamrock Shore or Dolores Keane with Galway Bay (for which Frank supplies its full title, My Own Dear Galway Bay).

However, any such familiarity should be discounted when listening to The Hungry Voice for Frank Harte has compiled an estimable collection and pressed his own distinctive imprimatur on the songs it contains. Whether the latter is always a benefit is open to question. Ever since his early recordings for the Topic label[2], it has struck at least these ears that Frank is at his best when in declamatory singing mode. A song such as By the Hush offers full scope for this thanks to its relatively short phrasing, but one such as Poor Pat Must Emigrate where each line is longer tends to challenge his vocal range.

Perhaps the latter is unimportant, for the simple matter is that Frank remains firmly at the forefront as a narrative singer and all of the songs here are decidedly within that ambit. Certainly too, since Frank’s diction is always so clear, the import of each song’s lyrics is rarely dissipated.

There is one questionable inclusion and that is the closing song, City of Chicago, which was written by Barry Moore to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Black ’47, the worst year of the Hunger (and recorded both by Barry under his stage alias of Luka Bloom and by his brother Christy). It does seem an oddity, not least because its lyrics are far inferior to, say, a song like Lone Shanakyle, but also because Frank’s voice is clearly not suited to the kind of gentle swaying melody which Christy Moore can hold so well.

However, this does raise another issue. Anyone who has purchased either or both of Frank’s previous recordings, or read the MT reviews, will be well aware of his catch-all slogan “Those in power write the history, those who suffer write the songs”.

At the time of writing City of Chicago Barry Moore was in receipt of a lucrative record contract, so could hardly be numbered amongst the downtrodden. Similarly, the author of No Irish Need Apply (whom Frank neither mentions nor credits) was one John Poole, who made a living as a songwriter in New York, and the song was subsequently popularised by one of the founders of vaudeville, Tony Pastor; neither can be termed “sufferers” and, by their names, were unlikely to be of Irish origin. Additionally, My Own Dear Galway Bay was composed by Francis A. Fahy who emigrated from Kinvara to London in 1873 and wrote a number of other popular pieces, including The Old Plaid Shawl.

There is too a noticeable absence of any Irish-language famine songs. This should not be regarded as surprising since Frank’s entry on the subject of hunger songs in The Companion to Irish Music fails to mention any at all. Yet these were written and include Na Prátaí Dubha[3] (whose translated first two lines are “The blighted potatoes have scattered our neighbours, There’s some in the poorhouse, some gone overseas”) and An Bhuatais[4] (whose title, ‘priest of the top-boots’ refers to a clergyman who cared more for his own well-being and appearance than his parishioners’ health). The author of the sleevenotes for the album on which the latter appears, Tim Dennehy, informs his readers that “Surprisingly few songs remain in the Irish language concerning the Great Famine”, but one would be hard-pressed to know that any survived at all from Frank Harte’s The Hungry Voice. Similarly, the album does not include any Irish-language songs about emigration and there really are plenty of these.

Whilst not suggesting in the slightest that an English-language singer, such as Frank, should suddenly start performing in Irish Gaelic, it is odd that there is nary a mention of the existence of these Irish-language songs. This is especially important as those who suffered most during the Hunger and, if they had managed to gain passage in the coffin ships to Canada or the USA, were often treated abominably by both the boats’ crews and, on arrival, by immigration officials, were the native-speaking Irish.

However, by focussing on emigration songs there is another point which the 56-page booklet accompanying The Hungry Voice (naturally, researched and written by Frank) fails to address. In his own entry on the subject of such songs in The Companion to Irish Music John Moulden cogently makes the point that emigration “songs tend to show what people thought happened rather than what actually did happen”[5] My Own Dear Galway Bay bears out John’s point since its author never visited the continent although Frank argues that “the song does faithfully reflect the loneliness experienced by many emigrants who had made a decent life for themselves and their family in America”. Well, actually, that is a major assumption. The song might simply be taken as a universal statement of people’s desire to return to their roots. The fact that the second line refers to Illinois cannot be disputed, but it might be argued that there are very few place names that offer the chance to rhyme, albeit awkwardly, with a phrase such as “roamed a boy”.

Said booklet begins with a concise and generally accurate account of the Hunger’s origins and effects. It must be reiterated, however, that Frank Harte is not a professional historian and that becomes clear in a number of ways. For instance, he refers to London’s The Times newspaper as being “always unsympathetic to the Irish”. This would be the same publication that printed an article on June 26th, 1845 containing the following paragraph:

They are suffering a real though artificial famine. Nature does her duty; the land is fruitful enough, nor can it be fairly said that man is wanting. The Irishman is disposed to work, in fact man and nature do produce abundantly. The island is full and overflowing with human food. But something ever intervenes between the hungry mouths and the ample banquet.

Though the newspaper’s views changed dramatically during the course of the famine, the words above could by no means be considered “unsympathetic to the Irish”.

Additionally, while Frank does refer to the fact that the potato blight of the 1840s also afflicted other European countries he fails to mention, firstly, that the British government’s agricultural and land ownership policies were imposed upon virtually all of its colonies (in India alone some twenty million people died from hunger during the second half of the Nineteenth Century) and, secondly, that its laissez-faire attitude applied equally at home. For good reason the 1840s were known for some time afterwards as the “Hungry Forties” in Britain:

Greedy or bankrupt landlords began to ‘clear’ their uncomprehendingly loyal tribesmen from their land, scattering them as emigrants throughout the world from the slums of Glasgow to the forests of Canada. Sheep drove men from the hills, and crowded a growing population, increasingly dependent on potatoes for their subsistence, further into pauperised congestion. The failure of the potato crop in the middle forties produced a miniature version of the Irish tragedy of the same period: famine and mass emigration which led to progressive, and until the present unbroken, depopulation. The Highlands became what they have ever since remained, a beautiful desert.[6]

The impact upon the Highlands of Scotland was immeasurable, but Britain’s economic policies drove many in other parts of the land into the workhouse and there were ballads written, such as The New Gruel Shops which recounted this experience.

It was not only in Ireland that the name of Lord John Russell, the Whig Prime Minister from 1846 to 1852, was detested:

There’s Campbell and Lord John

have plenty of store,

The blood of poor creatures

will be placed at their door;

Must be called aside, no matter

how soon,

And swept off the earth with

that cursèd old Brougham.[7]

It is astonishing too that Frank makes absolutely no mention of the Young Ireland movement other than a paragraph in the section on the song By the Hush explaining the lyrics’ reference to General Meagher and even then the coverage is derisory. There can be no question that the Young Ireland-led uprising of 1848 was catalysed in part by the Hunger. One of its leaders, James Fintan Lalor, was demanding not only a repeal of the Act of Union but an agrarian revolution. Another, John Mitchel had often railed against the iniquities of Britain’s policies towards Ireland, a country “producing sufficient food, wool and flax to feed and clothe not nine but nineteen million people”[8]

The uprising was further inspired by the overthrow of the French king Louis-Philippe in February, 1848, a year which also saw rebellions in other parts of Europe fuelled by agrarian dissent. In Britain, Lord John Russell was so alarmed by the situation in Ireland that he sent his Lord Privy Seal, Lord Minto, to the Vatican, a visit which resulted in Pope Pius I issuing a Papal Rescript admonishing the Irish priesthood for its political activities. Mitchel, Meagher and another Young Irishmen, Smith O’Brien were arrested in March that year and charged with sedition, but were later released on bail. The last two named above went straight to Paris to seek support from French republicans, but little happened except that the Acting President, Alphonse de Lamartine, “presented Smith O’Brien with a tricolour modelled on the French flag (to Meagher’s design) of Green, White and Orange, symbolising an eventual unity between the Orangemen and Catholics”[9] This later became the flag of the Irish republic.

Forgive the lengthy account, which some might regard as digression, but the lack of a connective internationalist perspective does suggest a fundamental flaw in Frank Harte’s historical method. Furthermore, it is intriguing that his lengthy bibliography, printed at the end of the liner booklet omits one of the most important recent publications on the years of the Great Hunger, Christine Kinealy’s This Great Calamity (a book which resolutely seeks to unravel fact from fiction through a thorough dissection of primary source material) and, in terms of emigration, ignores Tim Pat Coogan’s remarkably detailed Wherever Green is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora.

That last point is telling because, for Frank, the story of emigration is almost entirely one which concerns those who left Ireland’s shores for North Amerikay. The songs selected to form his musical account pay little, if any, attention to those who opted to depart Ireland for, say, Britain. Such songs do indeed exist. The Maid of Culmore, for instance, begins with the line “Leaving sweet lovely Derry for fair London town” (earlier versions had “Londonderry” rather than “lovely Derry”).

Frank is obviously no Janus. The front of his head cannot be looking ever westwards across the broad Atlantic while the back eyes the lands across the Irish Sea. However, it is the combination of his America-centrism and his failure to glance eastward that ultimately mars his written account of the Hunger years and makes his choice of songs to represent emigration decidedly and ideologically contentious.

That being said, the notes on the songs are, for the most part, highly informative and well-researched, reinforcing the feeling that such rigour should have been equally applied to Frank’s historical account.

Musically, this is one of Frank Harte's most coherent albums, thanks both to his delivery of the songs and Dónal Lunny's much understated accompaniment. However, listening to it is a chilling experience for those of us born British and reminds us that our ancestors might not have caused the Hunger, but they certainly exacerbated its impact.

This review by Geoff

Wallis was originally written for Musical Traditions - www.mustrad.org.uk.